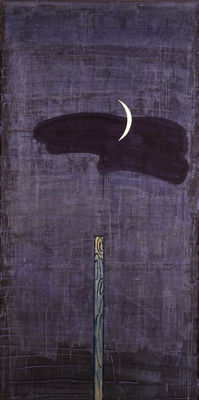

The Kite

Posted by Megan Arkenberg 0 comments

By: john w. sexton

The Storeroom of Grief

Beneath the dark winter clouds a fluid ball of starlings was shifting the evening nearer and nearer to the earth. Presently he found himself at the Tree of Exchanges, an ancient whitethorn burdened with a crop of haws. He snapped a thorn from the tree and scored the thick veins in the back of his right hand. On the mossy trunk of the tree he rubbed in the blood.

He stepped forward and looked at the sky, where he was told the Keeper of Hearts would be found. In the distance the starlings began to increase the volume of their communal piping.

He watched them closely now, moving east and west through the sky. The squealing whistle of their grouped voices increased considerably, until he realised beyond doubt that the massing cloud of starlings was getting closer and closer. The sky was dark with them now, until the sky was them.

And now as he watched, the starlings condensed into an urgent ball of many millions of bodies, tighter and tighter until it was as if a small feathery planet was hovering above him. A smaller ball of starlings, the size of a hut, broke away from the main body and flew in a swirling vortex towards him. As the ball reached the ground the starlings suddenly broke their formation, heading back in groups to their fellows above. As the smaller mass of starlings dissolved in this way they revealed at their centre a small dark woman. Her face and head was covered all of feathers, and her body also; and she was thus in no need of a coat or cloak. Her hands and feet were clawed, but with long delicate talons that shone in the dusk. Her face was that of a bird, and she began to address him in the whistling, rattling, clicking notes of a starling.

He had no knowledge of her language, but thoughts began to intrude in his mind and he understood quite clearly that she wished him to state his business. He told her that he wished to rid himself of his heart, for it was soaked with grief. She stepped forwards and took a hold of him by the waist. A shiver ran through him, a moment’s uncertainty. But of a sudden the air about him was thick with birds, and he was carried into the sky in a dynamic channel of movement. The Keeper of Hearts held a hold of his waist and sang out aloud in the communal cacophony of the cloud of starlings. And although the body of starlings was dense, he could still see through it, for it was layered and complex, with shifting windows of sight. He could see the heath below, and then the miles of headland and then the open sea. They were moving at a tremendous pace, and in swirling arcs; but he felt no discomfort, for it was like being in the hold of a living vehicle. And it dawned on him then that that’s exactly where he was.

Below him now was nothing but cold ocean, and he saw that they were descending towards it at great speed. The cloud of starlings entered the water in a frenzied cyclone of turning, and the waters parted at their entry. From time to time he could now see the innards of the ocean itself, great schools of fish, even once a whale as large as a palace. He began to feel cold now, and an intense pressure was squeezing him in its grip. Then suddenly there was quiet.

The starlings broke away without a sound and disappeared into darkness. He was in an underground chamber, alone with the Keeper of Hearts; this was the centre of the world, the Storeroom of Grief. In her hand she was holding a strange jelloid, pallid and limp. He recognised it now as a jellyfish.

Then his mind became dark and he was standing back at the Tree of Exchanges. The heath was troubled by a fresh breeze, and the moon was now very high in the night sky. No bird or sound of birds was in evidence. He felt calm, utterly unburdened; for his heart was gone.

Pulsing in his chest was a jellyfish, living in the inner ocean of himself, alive in the totality of his blood, which was now clear and unsullied by hurt. The path home would be short, for life would be long.

John W. Sexton lives in the Republic of Ireland. His sixth poetry collection, Futures Pass, was published by Salmon Poetry in 2018. A chapbook of surrealist poetry,

Inverted Night, came out from SurVision in 2019. He is a past nominee for The Hennessy Literary Award and his poem The Green Owl won the Listowel Poetry Prize 2007. In 2007 he was awarded a Patrick and Katherine Kavanagh Fellowship in Poetry. His poetry and fiction is widely published and some has appeared in Apex, Dreams & Nightmares, The Edinburgh Review, The Irish Times, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Mirror Dance, The Pedestal Magazine and Strange Horizons.

Where do you get the ideas for your poems and stories?

Folk and fairy tales, located as they are in a kind of indeterminate everyplace, have always drawn me. In all of the best ones there is an underlying emotional center that exerts its pull on the story and on the reader. When I first discovered the work of the fabulist Harlan Ellison in the latter-half of the 1970’s, I recognized that his stories resonated in the same way. I also felt in them a kindred connection to poetry, for they often had embedded in them many of the techniques of language that one normally associates with poetry in its many forms. His tales from that time and all the way into the 90’s exerted a fundamental influence on a lot of my attitudes to storytelling. In that spirit I’m dedicating this short piece to his memory - he died in 2018 , on June the 28th, at the age of 84.

A personal aspect of this particular story, however, is my artistic identification with the Aisling tradition of East Kerry and West Limerick, where both sides of my family are from. The Aisling is a form of vision poem. When it was first promulgated it represented political and nationalistic aspirations for a country under vicious Colonial rule, but it owed its origins to earlier goddess worship. It is in the latter, pagan sense that I associate with it. One of the principle figures of the Aisling is an Spéirbhean, the Sky Woman. It is the spirit of an Spéirbhean, albeit in a very personal interpretation, that partly informed and inspired my story of the Storeroom of Grief.

Posted by Megan Arkenberg 0 comments

By: john w. sexton

The Last Garden

by John W. Sexton

In the cottage lane there are nine front gardens; all of which you’ll have to pass if you wish to visit the rain. The rain is kept in the mumbling sea at the bottom of the lane. It is sought usually by the parched, or the heartless in need of light. For the kind of light you find in rain can’t be found anywhere else; it’s the kind of light that’s dark or bright at its own whim.

The first garden is a massive head of lavender with no break or seam. How one can pass it to the front door of the house is a secret; a secret not even known to postmen, nor to neighbours or even dogs or cats. Only the birds can pass over it, or the butterflies; moths can be shaken awake from it; earwigs know the tight rooms of it. The scent of it can entice you to its threshold, until, days later, you’ll find yourself still there, many days hungrier and fogged in memory.

The second garden is rough with failure, thistles shoulder to shoulder, many of them long-dead and brittle, their heads exploded into white fluff. Only snails venture in there, for the roots of the thistles are damp with rot.Paradox grows in that garden, for when a breeze rises, the seeds of the thistles will lift up and catch the light as they drift on. But a breeze rarely comes. Anyone stopping at the garden gate is want to hang their heads, and often there will be huddles of the despairing on the threshold of that garden. But days later they will be gone, thistles sprouting where they stood.

The third garden is crowded with black-eyed Suzies, all nodding their gold heads, and all of them holding the gaze of anyone who looks. In their black eyes there is something like a stairway up into the stars. There it winds, all the way up through the night, its banister steady. You’ll never fall on those stairs, so keep climbing; up you go, up, up, up. The stars are closer now, close enough nearly to catch, just a few more steps. And look at all those foolish old men, staring into that garden. They’ve been there since they were boys, with no need to eat or sleep. For the stars feed them as they climb those broadening stairs all the way up through the night, all the way up through their lost lives.

The fourth garden is all privet, with a gateway of hedge and a hedgehog; a hedgehog that is always entering the hedge anytime anyone passes. And the gateway of hedge is always in a different spot; sometimes to the left, sometimes to the right, sometimes dead in the centre. And of course, what child could possibly pass without following that hedgehog? Butparents don’t like that prissy hedge; they hate it, they know it has to be mean. So they’ll follow their child; but the hedge will turn and turn and turn, and their child is somewhere in that twisting maze of privet; they can hear the laughter.

The fifth garden is orderly and bright, and full of indigo roses. A deep indigo almost black when the light is dim; but in full sunlight the indigo roses are a summer’s night. What woman could disdain the gift of such a rose? Surely any woman will fall immediately in love with any suitor who presents her with such a thing? And so you will reasonably think as you pluck one for your sweetheart; even a woman who despises you will be enthralled with such a gift. And so you will take a second, and then a third, and then a fourth and a fifth, and on and on until your arms are burdened with indigo roses, their deep scent the conviction of a true memory, when all things were simple and good. And you will pluck another, and another, not mindful that your hands are raw from grasping the thorns, not mindful that you are deeper and deeper into the garden; not mindful that the indigo bushes are towering over your head; not mindful of the thorns tearing your face, of the thorns taking your eyes; but lost in the conviction of a true memory, of roses redder than the sun, of sunlight searing and pure.

The sixth garden is low and wild, a statement of green. Grasses, sedges, ferns, all a-bustle in a verdant chant. A cooling calm from that low wild garden will draw you in, and yes, there are people in there before you. You can hear them whispering. You want to hear what they are saying, for you know that it will be utterly profound. So you step into the grass, through the ferns, and oh, up all around you are moths, fluttering lazily. Their bodies are gold or silver, and they rise in their thousands like soft coins. They flutter upon you and you are enchanted. They flutter upon you in their hundreds and you are covered in gold and silver dust. Then they clothe you in their thousands and you are a garment of wealth. You step further through the grasses and ferns, and more and more moths rise up, and now you are a walking fortune of silver and gold. Deeper and deeper you enter the garden and your wealth is as vast as the sky, as unending as the cosmos. As innocent as moths.

The seventh garden is a gentle brae, with the promise of a house on its height. Rising over the brae is a plume of white smoke; and on the brae, suddenly, cowslips. What freedom, a young man or woman will think as they step upon that green slope. Just a few steps and you’d be at the top. But at the top: a wonder. All above you, in terrace upon terrace, are wide meadows of cowslips. And look, sitting down in the meadows are cows, their dark enormous eyes full of submission. You step amongst them and they begin to rise, and you notice that their udders are heavy with milk; so much milk that some is dripping to the grass. You sit down on a low boulder, the better to see these swollen udders and their flowing teats, and at your feet you notice a bucket. You’ve never milked a cow before and you are intrigued. You place the bucket between your legs and a cow sidles up. This milking, it’s so easy! You pull at the teats and feel the warm milk splashing up against your hands. When the bucket is full you put it down. What a great help this will be for the farmer. All around are buckets full of milk, many hundreds of them. The cows are making their way up through the terraces of meadows, as many cows as there are buckets full of milk. Your arms are weary, but what a delight this has been; you’ve been milking for hours and they’ve flown, flown like seconds. What a great help this will be for the farmer. You make your way down to the edge of the brae; and spread out below you, without any sense of horizon, are miles and miles of terraced meadows.

The eighth garden is dense with decaisneas. Any who would know this plant might guess it is autumn, for the tall shrubs will be heavy with the long blue pods. But there are no seasons in this lane, only the seasons that the gardens need there to be. But the chances are good that you won’t know this plant. It’ll be a mystery to you. You’ll look at those vivid blue pods and you’ll shiver a bit. Then it’ll come to you. Dead Man’s Fingers, you’ll think to yourself, and you’ll be right. And then you’ll think, this plant is from China, and you’ll be right again. How delighted with yourself you’ll be, knowing so much about something you know nothing about. And then you’ll notice that the pods are splitting already, and you’ll see them opening up. Dripping from the pods is a clear, phlegm-like liquid. How horrible, you’ll think. And you’ll be wrong. For this liquid is sweet. Go on, you’ll think, just the tip of my finger, what harm could it do? And you’ll be right. What harm could it possibly do? And you’ll dab your finger to your tongue. Oh, you’ll think, and oh and oh! How sweet! How watermelon sweet! And then you’ll be splitting the pods with your thumbs, exposing the black beans sitting in their clear phlegm. You’ll slurp out that juice, you won’t be able to get enough of it. And you’ll be spitting those beans all over the garden; all over your clothes. But then you’ll notice. What will you notice? The beans will be squirming. And fidgeting and fodgeting. And toing and froing. And flittering and flottering. For these little beans are fairy foetuses, little sprites not long conceived. Oh, but you’ve swallowed one? Ah, no need to worry. These little sprites like nothing more than to wear a person. They’ll take you for a stroll, they’ll take you on an adventure. But where will they take you? Perhaps there’s a garden in the lane you haven’t been to yet?

The ninth garden is utterly devoid of any plant or blade of grass. The bare earth is rife with a stink of piss, a piss so intense it could sterilize the air. The garden is bordered by a low wall and a broken gate, its metal grille eaten through with rust, with hardly any metal left to it, just a frail ghost of a metal gate. You could wait here for days, or even weeks, if you were foolish enough, and you’ll not see a single cat venture onto that low wall, or indeed venture anywhere near. Hardly surprising, you’ll realise, once you see the sign by the gate, with its black-lettered warning of BEWARE OF THE DOG. But you could wait here for days, or even weeks if you were foolish enough, and you’d not hear a single bark or whimper. But if you cast your eye down the bare path, all the way to the black lump of a house, with its dense black walls as dark as soot, walls that seem to breathe, seem to heave in and out, you might not be so foolish as to take a step beyond that piss-rusted gate. And if you have any sense at all, just a smidgen of sense will do, you’ll turn on your heel and make your way back down through the lane. Most people have done exactly that. But sadly, very few have ever turned on their heels and gone out of that lane without dawdling, without dawdling at the gates of one other of those gardens.

As for the rain, it is reputed to reside at the end of that lane, in a sopping, mumbling sea. Many have heard it, they say, complaining in its sleep, bemoaning its life and troubles; but very few have actually seen it beyond a glimpse. And there are some who claim it’s actually a garden itself, a tenth garden; but none have gotten close enough to be sure.

John W. Sexton lives in the Republic of Ireland and is the author of six poetry collections, the most recent being Futures Pass, which was published by Salmon Poetry in 2018. He is a past nominee for The Hennessy Literary Award and his poem The Green Owl won the Listowel Poetry Prize 2007. In 2007 he was awarded a Patrick and Katherine Kavanagh Fellowship in Poetry. His poems are widely published and some have appeared in Apex, Dreams & Nightmares, The Edinburgh Review, The Irish Times, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Mirror Dance, The Pedestal Magazine and Strange Horizons.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?

From the age of about eight until I was sixteen my family lived in a part of North London between Turnpike Lane and Finsbury Park. We lived at that time in a house in Fairfax Road, and all the adjoining roads were connected by an alleyway that ran middle-ways between them all. A few streets away, in Frobisher Road, right on the corner beside the alleyway that divided that road in two, there was a house with a high wall that ran into the alleyway. Beyond the wall, which we often stood on as a dare, was a wild garden. The weeds were so high in the summer months that if you fell into them you’d imagine you’d disappear. And everyone had it that in that house lived an old witch. She was famous through all the adjoining streets as the Frobisher Road Witch, and some said she wore clothes of grey with a grey hat, but many had it too that she sometimes wore pink with a pink hat.

Of course, it was very difficult to find anyone who claimed to have actually seen her themselves, for it was always someone else who had told them they’d seen her. Every single report about her existence was second-hand and from third parties, and in all the years there I never saw her myself. The curtains in the windows were so grey that they looked like they were made of dust. We would often sit up on the high wall looking into the garden, hoping that the witch would come out so that we could see her. She never came, much to my relief. I think that perhaps everyone was relieved that she never came into the garden, but we wore our bravado stubbornly and often sat there for ages. Not once, in all those years, did anyone venture down into the garden itself. It was as if the weeds threw out a barrier to ward us off.

And from that time I have been fascinated with both the beauty and the strange loneliness that even the most wonderful garden can appear to be imbued with. Wild or pristine, gardens have a mystery about them, and “The Last Garden” is a kind of meditation on all those mysteries I have found in all of the gardens I have entered. And sometimes, sometimes long after we have left a garden, we feel a longing to go back there, as if a part of it still lingers within us.

Posted by Megan Arkenberg 0 comments

By: john w. sexton

The Constant Stranger

My face is the lake in which I drowned.

The moon’s reflection is the clasp of my cloak.

When there is no moon visible my cloak is held

by the dark of the moon; my hair is the river run inwards.

The silted floor of the lake is the chatter

fallen from my head; my lashes are reeds on the shore.

My lips may never open but my eyes are never closed.

The dead can never hurt from lack of a kiss.

Stone is the stillest and calmest of sentinels. The mountains

hold my face in their gentle grasp.

The most essential ingredient for the incredible is the credible. For the unbelievable to be believed it must to some large extent appear believable in essence. The best way to achieve this often is to introduce the shadow of metaphor. Metaphor gives purpose to the Fantastic, and purpose more easily persuades the doubting mind than any other element.

Posted by Megan Arkenberg 0 comments

By: john w. sexton

Lady of Lullaby

Our eyes are heavy with sleep

The moon falls from its socket

And nothing is ours to keep

Sunbeams burn holes in our pockets

Moonbeams burn holes in our shoes

Stars unscrew from the heavens

And angels are yesterday’s news

So sleep on your pillow of feathers

Fear nothing that falls with the snow

The meadows are white in the moonlight

The night is heavy and slow

A woman steps lightly through starlight

She kisses you now while you sleep

The moon falls from its socket

And nothing is yours to keep

John W. Sexton lives in the Republic of Ireland and is the author of five poetry collections, the most recent being The Offspring of the Moon, which was published by Salmon Poetry in 2013. He created and wrote the science-fiction comedy-drama, The Ivory Tower, for RTÉ radio, which ran to over one hundred half-hour episodes from 1999 to 2002. Two novels based on the characters from this series have been published by the O’Brien Press: The Johnny Coffin Diaries and Johnny Coffin School-Dazed, which have been translated into both Italian and Serbian. Under the ironic pseudonym of Sex W. Johnston he has recorded an album with legendary Stranglers frontman, Hugh Cornwell, entitled Sons Of Shiva, which has been released on Track Records. He is a past nominee for The Hennessy Literary Award and his poem The Green Owl won the Listowel Poetry Prize 2007. In 2007 he was awarded a Patrick and Katherine Kavanagh Fellowship in Poetry. His poems are widely published and some have appeared in Apex, Dreams & Nightmares, The Edinburgh Review, The Irish Times, The Pedestal Magazine, Rose Red Review, Silver Blade, Star*Line and Strange Horizons.

Where do you get the ideas for your poems?

Children are naturally creative and magical. When you are young, and still have faith in the world of invisible powers, anything is possible, and the most unbelievable events might even be likely. When Hansel and Gretel wandered into the woods, a house baked like a cake and with windows of spun sugar was not in the least unexpected. When the elderly and childless couple found an enormous peach floating down the river, what else would be at its centre but a baby boy? The very common propensity of young children for magic and for entering the domain of the Other was one of the two seeds behind “Lady of Lullaby”. The second seed was the charm that lullabies have cast upon me from childhood. The power of the lullaby cannot be underestimated and originates from practical magic. These beautiful little chants were used from the earliest of times not simply to make children safe in their beds, but more importantly, to convince children that they were safe from every danger that lurked in the night before one wakes. In that way they operated essentially as prayer. As a poetic device lullaby is not as popular as it once was, but many poets still utilize its power, most recently the late Leonard Cohen, and from the middle of the last century the poets James Agee, W. H. Auden and Sylvia Plath, amongst others. As a poet, company such as theirs is what I aspire to, no matter how hopeless that aspiration may be for me.

Posted by Megan Arkenberg 0 comments

By: john w. sexton

The Mouse

While the saint was asleep a devil crawled out

from the dying coals of the fire. He scraped his feet

clean on the grate and shook sparks from his skin.

Embers of his flesh fell about the room, even fell

onto the blanket covering the snoring saint; but all were

immediately dampened by some hidden force.

The devil snorted. Saints were the pain in his pointed

tail. He hated them. Especially this fool snoring peacefully,

too stupid even to know that Evil was afoot in his room.

Something stirred by the saint’s ear. The devil hoped

it might be the soul of the saint, so he snatched it up.

But it was merely a mouse, trembling now in the devil’s

grip. On the translucent tips of the mouse’s ears the devil

could see a kind of light he’d never seen before. A light

more subtle than any light found in Hell. The devil hated

any kind of subtlety but the mouse carried his without

either arrogance or holiness, so he released it down onto

the floor of the room. The mouse scurried into the shadows.

The devil looked at the snoring saint; a saint more from

lack of temptation than sainthood; a saint of prayer

and mumbling. There wasn’t much here for the devil to take.

The devil could sense rot in the walls, the perfect vehicle

to travel by. With his body now as black as the deepest

shadow the devil stepped into the wall. The wall took to him

at once. In the now peaceful room the mouse emerged

from the skirting, the wall no longer a place for him to be.

The embers of the fire began to stir and something rose

from the dying coals. An angel grey as smoke

stepped into the bedroom, her wings opening out wide.

Still snoring, the saint slept on. The angel reached down

and picked up the mouse. On the translucent tips of the mouse’s

ears the angel could see the light that had long ago shed

from her wings. Here was her gift to the Earth. She looked

down at the sleeping saint, one only in the eyes of men. One

with not yet the innocence of the mouse, one not yet with

the resolute integrity of a devil. A long way yet until this saint

would ever be fit for the deep places of Heaven, where light

was given to mice and darkness was prized above all else.

When I was a young boy I was entranced by tales of saints and their miraculous deeds. To my innocent mind they were no different to the super heroes and heroines that appeared in the comics I was then reading, and in common with them they were always on the side of the poor and the downtrodden. The only difference between them was that at the time, being brought up as a good Catholic boy, I thought such tales were straight historical accounts, because that’s how they were presented to us then. It was only as I grew out of such things that I viewed them properly: as myths containing spiritual truths and insights.

In “The Mouse” my intention was to invert that kind of story, but not as a mockery of such myths, but rather as a personal tribute to them. For, from the very beginning, they were an important personal foundation not just for my creative mind, but for the creative heart as well.

Posted by Megan Arkenberg 0 comments

By: john w. sexton

The Allotment above the City

She carries her autistic son with her, sewn to her heart.

With her every heartbeat he dances in her breast;

she’s bruised to nothing from his dancing.

Red speck by red speck, ladybirds alight

on her shoulders and all down her back,

a collar and cloak of enamelled glistening.

An old man looks up from his row of cabbages

and offers her a thousand caterpillars.

“Accept this gift and save my garden,” he says.

He pours the caterpillars over her head

and they begin to spin silk.

Under her veil of silk and caterpillars,

with her collar and cloak of ladybirds,

she proceeds down the path.

Her son continues to dance,

dances a coagulating blood at her heart.

A young girl stands in her way where the path narrows.

In her cupped hands she holds a quivering jelly of frogspawn.

“Accept this gift and save me from unwanted births.”

She pours the frogspawn from her own cupped hands

and into the mother’s cupped hands.

The aged mother continues down the path.

The sky is tearing in the last of the sunlight.

The aged mother steps forth;

in her clothing of sacrifice she is ready for the dusk.

The child at her heart spins on his feet.

From the hedges the songbirds are singing her an answer;

they sing her the solution of her passage.

They sing her the route through the encroaching darkness.

But birdsong is a language beyond her.

At her heart her son is dancing himself loose,

the heart’s stitching is easing apart.

The aged mother stops - then with her teeth

she pulls the stitching tight;

for though beyond birdsong, she knows

that her son needs to be close to her always.

The birds sing her the knowledge she needs,

but love is the answer she finds in herself.

Carefully she continues to hold the frogspawn in her hands.

She will hold it until it is ready to be set free in the pond.

Dusk falls and then night falls on the allotment.

In the darkness the vegetable plots lie still,

forever beyond her, as useless as birdsong.

Our pasts often inform how we think. I will try to articulate it by the following.

Over thirty years ago, at the age of 18, my brother Gerard and his friends thought that it would be a thrill if they stole a car. So that’s exactly what they did. In the excitement of drink and youth they tore through the night-time streets of London in a car they had taken from a pub carpark. It was to be the last thing my brother would ever do, for he died as a direct result of taking that car. The car also failed to survive the night, so in the cold calculations of matter, the sacrifice of each cancelled out the other.

My eldest son, Matthew, was also involved in some form of collision, of a nature unknown and unknowable, except that the vehicle in which he traveled was the womb of his mother. When our son Matthew finally emerged, he arrived in a world not his own. Being autistic, he found himself in this place of clamoring.

Pain is the special language we utilize in order to communicate with the godhead. We not only suffer in the universe, we suffer with the universe. Indeed, we suffer as the universe.

Poetry is a poor and imprecise language in which to articulate our struggles. But it is the only language a poet knows. Thus, in poetry, I speak to whoever might listen. I speak as loudly as I can, in this place of clamoring.

Posted by Megan Arkenberg 0 comments

By: john w. sexton

Aisling and the Whalecat

by John W. Sexton

Once, once, long ago, forty miles beyond the Great Skellig, was an island called the Skellig-of-the-heart. Very few could find exactly where it lay, and only the most skilled of sailors could land upon it. Some claimed it was made of fog, some that it was made of ice, some that it was made of glass, some that it was made of rain, and others swore it was made of light.

But those who had secured their boats to it swore that its shores were firm and could hold a thousand men. And on that Skellig-of-the-heart there lived a young girl. And in all the hundreds of years that men claimed to have met her it was said that she never aged a day. Ten years of age she stayed, for a thousand years.

And then one day she aged one day and the world was changed. And this is the story of that single day.

Once, once, long ago, on the Skellig-of-the-heart, there lived a girl called Aisling who was ten years of age. She had been that age for a thousand years for she lived on an island as soft as fog, as cold as ice, as clear as glass, as pure as rain, as fresh as light.

And then one day she took a walk to a part of the island where she had never been. And there on the edge of the northern cliffs was a sight she’d never seen. For on the clear, glassy beach, there rose a dark hill. The hill was covered in black grass and rose higher than she could see. Aisling started to climb. The black grass at her feet was soft and warm and the wind blew pathways through its depths. And through one of these paths she walked to the very top.

At the top of the black hill Aisling found two flat ponds of water. One pond was blue and one was green. In the blue pond there swam a large green fish and in the green pond there swam a large blue fish. As she looked into their shimmering waters the ponds grew large, and when she looked again they were small. Then larger the ponds became, then smaller; then larger, then smaller; then larger again, then smaller again.

Aisling had never seen a thing so strange; ponds that grew and then shrank. Aisling watched the green fish in the blue pond. When the fish swam deep the pond grew small, but when the fish came up for air the pond grew large. Then Aisling watched the blue fish in the green pond. Likewise, when the fish swam deep the pond grew small, but when the fish came up for air the pond grew large.

Then Aisling heard a sound like howling wind, but a howling wind far greater than the gentle wind that blew pathways through the black grass at her feet. Curious, she began to walk towards the noise. Soon she came to two darkened caves, set deep in the black grass of the hill. Out of each of the caves howled a tremendous storm.

So great was each of the storms that a flock of seagulls was caught in their gusts. Then just as suddenly as they blew to sea, the winds changed direction and the seagulls were sucked down into the caves. After the seagulls ten eagles were sucked down into the caves with the howling wind, then a flock of puffin, then a dozen geese.

Then just as suddenly as the winds were sucked into the caves, they changed direction and were blown out to sea. Out of the caves flew a dozen geese; then out flew a flock of puffin, then ten eagles, then a flock of gulls. Then just as suddenly as they blew to sea, the winds changed direction and the seagulls and the eagles and the puffin and the geese were sucked back down into the caves.

And this went on and on and on, the winds forever exchanging direction, and the seagulls and the eagles and the puffin and the geese were thrown from the sea to the caves and from the caves to the sea. And Aisling had never seen a thing so strange.

And then Aisling, her ears throbbing with the howling of the wind, made her way down from the caves. Soon she came upon a large pit, set deep into the black grass of the hill. This pit was much greater than the caves and at its centre was a soft red fire. It was the strangest fire she had ever seen, for it was as warm as the summer’s sun and as wet as the winter’s rain.

Aisling had never seen a thing so strange, for she had never seen fire that could be both warm and wet. And along the edge of the pit ran a pearly staircase. The staircase described the circle of the pit and went up and then down, and then up and then down, and around and around as circles do, no single place its beginning and no single place its end.

Aisling stood on the pearly staircase and began to climb. As the steps went up they became long, and as the steps went down they became short. And down in the centre of the pit was a fire that was both warm and wet. And as Aisling climbed up and down the pearly stairs she had never been on a thing so strange.

Then Aisling heard a rumbling voice coming up from the pit.

WHO IS THAT TRAMPLING UP AND DOWN MY TEETH?

WHO IS IT THAT STARES DOWN AT MY TONGUE?

I CAN FEEL YOU, YOU TINY LOUSE, BUT I CANNOT SEE YOU FOR MY EYES ARE BLIND.

I AM THE WHALECAT. MY PURRING BREATH COMMANDS THE TIDES, MY TAIL SPANS THE WORLD.

BUT I AM STRANDED ON THIS SKELLIG-OF-THE-HEART, FOR A BLUE FISH IS IN MY GREEN EYE AND A GREEN FISH IS IN MY BLUE EYE AND I CANNOT SEE MY WAY THROUGH THE OCEAN.

AND THE IRRITATION IN MY EYES IS MAKING ME SNEEZE, AND THE SNEEZE IS BLOCKING MY NOSTRILS WITH BIRDS AND I CANNOT HOLD MY BREATH BENEATH THE WAVES, SO THE TIDES ARE WILD AND THE WORLD WILL FAIL.

And as Aisling stood on the pearly staircase listening to the voice, she had never heard a thing so strange.

Then Aisling called down into the deep pit of the whalecat’s mouth:

“My name is Aisling and I am ten years of age. I’ve lived alone on the Skellig-of-the-heart for a thousand years. I have no memory of how I got here but I’m lonesome for company and tired of sleeping out in the cold, exposed to the blizzards of the sea. If I help get those fish out of your eyes, will you promise to take me to a more wonderful place than this?”

HA, SO YOU ARE NOT A TINY LOUSE AFTER ALL?

YES, LITTLE GIRL, IF YOU REMOVE THE FISH THAT TROUBLE MY SIGHT I’LL TAKE YOU TO THE HIDDEN CORNERS OF THE SEA. AND YOU’LL SEE ALL THE WONDERS OF MY KINGDOM.

Then Aisling stepped off from the whalecat’s pearly teeth and made her way back up through his black fur towards his two eyes.

As she peered into the depths of the whalecat’s blue eye she could see the green fish, who was now rising up for air. So Aisling took the long golden hair on the left-hand side of her head and braided it into a plait. And when the braid was finished she lowered it into the waters of the whalecat’s blue eye. Then, with the long plait of her hair sinking into the water, she walked over to the whalecat’s other eye, and as she peered into the green depths she could see the blue fish, who was now rising up for air.

So Aisling took the long golden hair on the right-hand side of her head and braided it into a plait. And when the braid was finished she lowered it into the waters of the whalecat’s green eye.

Aisling waited until she felt the two fish tugging at the braids, which they had mistaken for golden sea-snakes, and then she began to walk up high over the top of the whalecat’s head, and then down over his long back. As Aisling walked on, her two braids of hair were pulled free of the water and out came the two fish with them.

As the fish left the whalecat’s eyes, Aisling could see that their bodies were incredibly long. They were like two wonderful eels, each a mile in length. Free of the water, they struggled and writhed on the black fur of the whalecat’s back. One was as green as the sea, the other as blue as the sky. And Aisling had never seen fish as strange as these.

Then, stranger still, the fish began to speak. And the green fish said: “My daughter, Aisling.” And the blue fish said: “Oh my daughter, Aisling.”

And both together the fish began to speak in unison.

“Aisling, you are our only child, our first and only daughter. We are the people of the sea, merrows from the depths. One day while we swam these waters, on the very day of your tenth birthday, we were caught in the nets of a fisherman. He slaughtered us like seals, for that is what he thought we were. With our last breath we made an island for you from the pure blood of our hearts’ love, and set you here where you’d be safe. Then our spirits entered into these two eels and we have been searching the ocean for a thousand years to find a guardian worthy enough to raise you.

“Before we set you here on this enchanted place we cleared your mind of every memory so that you wouldn’t be haunted by sorrow. Now we bring you the whalecat, to raise you as his child. Goodbye, young daughter, and love us all your life, for now we must depart to paradise.”

The two eels slithered off the whalecat’s back and down into the waters of the sea. Down, down, down they swam, and the Skellig-of-the-heart began to melt. And sitting in the black fur of the whalecat’s back Aisling began to cry for her dead parents. And she cried and she cried until the waters of the sea began to rise with the fullness of her tears.

And when Aisling had finished crying an entire day had passed. And the waters had risen and risen until the lands of the earth grew small, and the Great Skellig was nothing but the tip of stone that it is today, poking out of the ocean.

And the whalecat floated in the sea, the waves lapping against its fur. Aisling could see the whalecat’s tail, which stretched for miles over the water. After a time the whalecat curled this immense tail beneath itself, and was thus able to stand upon its floating spiral, as if standing on a raft.

On the tip of the whalecat’s tail there was a claw, a claw as long as the largest ship, and it curved sharply like a dredging hook. It was with this claw that the whalecat, whenever residing in the deepest parts, could anchor itself to the bottom of the ocean. But on this day the ocean floor was well below them, and the sun shone into the whalecat’s eyes, its green eye and its blue eye, and the twinkling of those great eyes could be seen from the distant land.

AISLING, MY ADOPTED CHILD, CLIMB INTO THE CHAMBER OF MY LEFT EAR. THERE YOU WILL BE SAFE AGAINST THE OCEAN, FOR WHEN I DIVE TO THE DEPTHS MY EARS FOLD CLOSE AGAINST MY HEAD. COME WITH ME NOW, AND YOU’LL GAIN ALL THE WONDERS OF MY KINGDOM.

So Aisling did as she was bid, and the great whalecat uncurled its tail and dived down into the cold waters. And since that time Aisling has not aged above ten years and a day, and she lives at the bottom of the deepest sea, curled asleep in the whalecat’s ear.

John W. Sexton lives in the Republic of Ireland and is the author of five poetry collections, the most recent being The Offspring of the Moon, which was published by Salmon Poetry in 2013. He created and wrote the science-fiction comedy-drama, The Ivory Tower, for RTÉ radio, which ran to over one hundred half-hour episodes from 1999 to 2002. Two novels based on the characters from this series have been published by the O’Brien Press: The Johnny Coffin Diaries and Johnny Coffin School-Dazed, which have been translated into both Italian and Serbian. Under the ironic pseudonym of Sex W. Johnston he has recorded an album with legendary Stranglers frontman, Hugh Cornwell, entitled Sons Of Shiva, which has been released on Track Records. He is a past nominee for The Hennessy Literary Award and his poem The Green Owl won the Listowel Poetry Prize 2007. In 2007 he was awarded a Patrick and Katherine Kavanagh Fellowship in Poetry. His poems are widely published and some have appeared in Apex, Danse Macbre, Dreams & Nightmares, The 2012 Dwarf Stars Anthology, Eye to the Telescope, Fur-Lined Ghettos, microcosms, The Mystic Nebula, The Pedestal Magazine, The 2012 Rhysling Anthology, Rose Red Review, Star*Line and Strange Horizons.

What advice do you have for other fantasy writers?

Genre is best seen, I believe, as a spectrum, rather than as a coagulating mass. So I think an early thing a writer has to decide is where they are on the spectrum. Another way of looking at it is to ask, what tradition of the Fantastic do I belong to or fit into best? Once a writer focuses on where they are they can function far more convincingly.

In my case I look at the genre through a specific set of lens, each individual lens being whichever tradition I am representing at any particular time, or upon which part of the spectrum I happen to be standing when approaching an individual poem. The traditions I align myself with, and all from a European perspective as I am a European, would be Magic Realism, Metaphoricism and Fabulism. As is common with the European practice of these particular isms, folktale is the specific myth-kitty that I would instinctively dip into. A very important additional approach that I align myself with, and this is specific to Ireland and to the geographical province I belong to, is the Aisling tradition, which is an Irish version of the vision poem. This sense of belonging to a tradition or traditions imbues me with creative confidence and also a conviction of artistic lineage.

In Irish poetry at the moment there is a crisis brought about by a top-heavy reliance on poems of the quotidian, which has led to convergence - where far too many poets are writing of common experience in a similar register. So what we have in Irish poetry journals is a bland porridge of the nearly same. As a poet working in the traditions of the Fantastic I am therefore currently and effectively anti-quotidianist, which suddenly legitimizes my stance as literary-political. This legitimacy is easier to maintain if one can claim a legacy of such writing. So my advice to writers is: find a tradition to belong to and then belong to it. Belong to it and serve it, and then take it further. It will deepen your writing immeasurably.

Posted by Megan Arkenberg 0 comments

By: john w. sexton

Your Next Journey of Eight Stops

by John W. Sexton

Herttoniemi:

Leave the train momentarily.

From the red dispensing machine select an item at random.

Give this to the beggar wandering deluded by the yellow line.

In return the beggar will kiss you on the right cheek.

The kiss will remain on your cheek for most of the journey.

Do not wipe it away. It will be needed later.

Return to the train.

Siilitie:

A crow will swoop into the train

and deposit a gobbet of snow into your left ear.

Do not remove the snow from your ear.

The crow will leave the carriage almost immediately.

Listen to the snow. Remember all that it tells you

Itäkeskus:

Even if you are already on the Vuosaari train,

exit the carriage and wait for the next train to Vuosaari.

If a woman with bronze hair asks you for the time

tell her that you will give her a year of your life.

If you are still alive when she departs along the platform

be grateful that you had more than a year’s life to live.

If from this point you are no longer on the platform

then you are most likely dead.

If you are still alive then enter the next train marked for Vuosaari.

Myllypuro:

On the platform the station master

will be holding a parcel of sunlight.

Those who look into it will become blind.

Those who ignore it are already blind.

With your eyes closed accept the parcel

and return to your train.

Puotila:

The round lights on the ceiling of the platform

will purr like cats.

The parcel of sunlight will become heavy.

All the mice of Puotila will have gone in there

to hide in the light.

No matter how heavy it is

do not remove the parcel from your lap.

Kontula:

The snow in your ear will describe a person

who has just entered the carriage.

The person the snow has described

will sit in the empty seat to your right.

Unbidden that person will lean over suddenly

and kiss you on the right cheek.

They are taking the kiss that was left there.

Say nothing. Do nothing.

Do not look at the person who has kissed you.

If you are a man that person will be a man.

If you are a woman that person will be a woman.

Rastila:

The person who kissed you at Kontula will leave the train.

As this person leaves their seat you will notice

that they have become a young child.

Do not be jealous that they are young again.

Do not question how this could be.

The last of the snow is now almost completely melted in your ear.

Remember the very last word it speaks.

Mellunmäki:

Depart from the carriage even if this was not your intended destination.

Leave the parcel on your seat.

Do not worry that the train might be overcome with sunlight.

Do not worry that the train might be overcome with mice.

The destiny of the train is not your concern.

Once the train departs the platform

then you must speak out loud the very last word

you heard from the snow.

What happens next is unfathomable.

But you’ll know it when it happens.

John W. Sexton lives in the Republic of Ireland and is the author of five poetry collections, the most recent being The Offspring of the Moon, which was published by Salmon Poetry in 2013. He created and wrote the science-fiction comedy-drama, The Ivory Tower, for RTÉ radio, which ran to over one hundred half-hour episodes from 1999 to 2002. Two novels based on the characters from this series have been published by the O’Brien Press: The Johnny Coffin Diaries and Johnny Coffin School-Dazed, which have been translated into both Italian and Serbian. Under the ironic pseudonym of Sex W. Johnston he has recorded an album with legendary Stranglers frontman, Hugh Cornwell, entitled Sons Of Shiva, which has been released on Track Records. He is a past nominee for The Hennessy Literary Award and his poem "The Green Owl" won the Listowel Poetry Prize 2007. In 2007 he was awarded a Patrick and Katherine Kavanagh Fellowship in Poetry.

What do you think is the attraction of the fantasy genre?

For me, as both a reader and a writer, the attraction of the Fantastic in literature has always been its ability for resonance. The fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen were the first to expose me to this resonance as a young boy. It was as if the stories themselves held a secret inside of them, something my reading mind couldn’t quite put its finger on. Tales like The Tinder Box, The Flying Trunk, The Steadfast Tin Soldier, held in their melancholy and disturbing undercurrents an irresistible tow that kept my imagination drowned in them long after I’d closed their final pages. It is that sense of after-drowning that attracts me to the Fantastic; it is that aspiration for resonance that keeps me writing it.

Posted by Megan Arkenberg 0 comments

By: john w. sexton

Entered in the Ledger of Night

What inspires you to write and keep writing?

When I was a young child I got the notion, I’m not quite sure how it began, that the headboard on my bed was sending me dreams whenever I slept. The headboard in those long-ago days of the first remembered house of my childhood was wooden and rectangular; it had a beveled frame along all four sides. In some way I think it resembled a television in my childish mind, and perhaps it was this association which inspired that first notion. Anyway, this idea that the headboard contained dreams began to take hold and I remember that on some nights I’d pull the bed away from the wall so that I could examine the back of the headboard itself. It was then that I discovered dust mites in disparate herds roaming across its dusty, neglected dark side. Instead of being repelled by them I was fascinated, and imbued in them a sort of guardianship. I imagined they were the carriers of dreams, crawling into me when I slept. I never crushed them beneath my thumb as I saw my younger brother do. I imagined further that they’d carry no dreams to him. I think it is still something so small, secretive and seemingly insignificant as a dust mite that continues to stir in my mind. I see them often here on my desk as I write, or crawling along the edges of my books. I rarely dust my office and have no desire that anyone do this on my behalf. What keeps me writing is an agitation in the mind, like an allergen. I am now so sensitized by it that my imagination fires continually under its bombardment, regardless of whether I am asleep now or awake. I can offer no answer to what keeps me inspired other than this, as strange or as unsatisfactory as some might imagine it to be.

Posted by Megan Arkenberg 1 comments

By: john w. sexton

Princess of the Hedgerow

An owl

a-freckle aflutter

a blackbird in each eye

a brandling worm

a bracelet worn

a beetle blue as sky

a blush

of red-leafed autumn

a voice of damson sweet

a bird’s nest nestled

in each ear

a birdsong so discrete

a dress of dew

a dress of snow

a dress of shining frost

a badger

half-a-moonface

his shadowed body lost

her hair is pinned

with thistles, her hair

is pinned with thorns

no money jangles

in her purse

only chinking stones

John W. Sexton lives in the Republic of Ireland and is the author of five poetry collections, the most recent being The Offspring of the Moon, which was published by Salmon Poetry in 2013. In 2007 he was awarded a Patrick and Katherine Kavanagh Fellowship in Poetry. His poems are widely published and some have appeared in Danse Macbre, Dreams & Nightmares, The 2012 Dwarf Stars Anthology, Eye to the Telescope, Fur-Lined Ghettos, microcosms, The Mystic Nebula, The Pedestal Magazine, The 2012 Rhysling Anthology, Rose Red Review, Star*Line, Strange Horizons, Sugared Water and Ygdrasil.

Where do you get the ideas for your poems?

Somewhere in my mind is a throne of woven, living blackthorn; its seat so jagged that no one can sit upon it in comfort. To reach it one must enter a tight blackthorn thicket, where the throne is indistinguishable as a throne. Being in such a crowded environment it has no space of its own. Picking it out as a throne, in all the tangle of other branches, and then easing into it to sit down, is the only way in which one can position oneself in order to see the absence of sky, not even a glimpse of which pierces the thicket itself. This is where I go to get ideas, within that forest of archetypes inside my head. This answer is probably neither clear nor helpful, but seated upon the blackthorn throne I can now become birdsong – enigmatic and mysterious. The greenwood of metaphor within our minds is the conduit for all poetry; and as a poet I would identify myself as a Metaphoricist.

Posted by Megan Arkenberg 0 comments

By: john w. sexton

_(14594613849).jpg/800px-Dictionnaire_pittoresque_d'histoire_naturelle_et_des_ph%C3%A9nom%C3%A8nes_de_la_nature_(1838)_(14594613849).jpg)