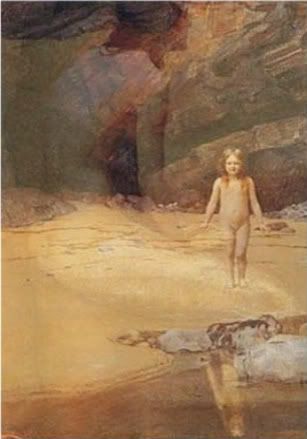

Water Girl

by Tyrell Johnson

Her skin sparkled like silver, a dazzling display of color against the dull fluorescent hospital lights.

The doctor pulled her from the water and she shone so bright she was hard to look at. He snipped the umbilical cord with his white, gloved hands, then passed Elya to me. I held my breath and took her into my arms, both of our bodies half submerged in the birthing tub. Something was terribly wrong, but no one said a word. As I held the luminescent child against my chest they all watched the light on her face recede to a dim glimmer.

The nurse pulled Elya from the water, dried and swaddled her in a soft blue cloth and laid her in the hospital crib, which looked like a terrarium for some exotic animal. We all stared like she was about to burst into flame and it wasn’t until the last tiny spec of light faded from her cheek that she began to cry.

When I was pregnant I didn’t have any weird sort of cravings. But that didn’t stop me from calling Jon and having him bring me all kinds of things. We weren’t together then, but he’d still bring me ice cream, pizza, olives, teriyaki chicken, peanut butter and pad thai. I hardly ate any of it, and after nine months my fridge was so stocked with food I didn’t know what to do with it all.

But I was often thirsty. I’d wake up in the middle of the night with my throat dry like leather and I’d waddle downstairs and drink glass upon glass of water. I never wet the bed or peed myself either, as I’ve heard happens with some pregnant women. It was like my belly was one giant tub of water. I’d press my hand against my stomach and when I felt her little kicks, I’d pretend she was swimming.

At first I thought it was some sort of allergic reaction. Perhaps something in the water was irritating her skin. Jon came to the hospital and sat with me in silence as the doctor tested her blood and dripped little beads of water from a dropper onto her arm. We all watched as they sparkled. Elya was squirmy at first, so I shushed her and held her tight, but when the water touched her skin she grew quiet and content.

“Good Lord,” the doctor said and pulled Elya’s glowing arm up to his face. He called the other doctors, who left their patients with fevers, infections, heart palpitations, and sexually transmitted diseases to come look at the girl with the diamond skin. They crowded around the room and mumbled excitedly when more drops were administered.

I was so upset I took Elya and stormed out, in my hospital clothes and everything. They called after me. They said they needed to hold her overnight, that they had more things they could do for her, medicine they could give her, experiments they could run. They pushed their cards at me but Jon and I just shoved our way through the white coats and double sliding screen doors. A few followed us into the parking lot, others shouted from their windows as I buckled Elya in Jon’s car and we drove away. The sound of the doctors’ jaws snapped after us.

Instead of baths, I wiped her down with a damp towel and dried her as quickly as I could. It didn’t do a whole lot and since I lived on the beach she began to smell like the ocean. When Jon came to visit he’d take her outside and rock her on the porch. I’d stand by the screen door and watch the unraveling waves and imagine long watery arms reaching out for her. He’d sing and I’d listen as he did, thinking that I didn’t know he could sing, and that he never sang when we were together.

When she was three she dunked her hand in a glass of water. I had left the glass in the middle of the table like I always do, and she was in her room taking a nap. I had the TV on when I heard her giggling. She had climbed onto the table, and dunked her hand into the glass. Her palm lit up like a light bulb, then grew translucent, melding with the water as little streams spilled over the edge and gathered into pools on the table. By the time I got to her I couldn’t tell what was water and what was skin. I pulled her off and ran for a rag. Her hand dripped, then slowly came back into focus, then glistened and shone like so many tiny lights before it finally went back to normal.

“Tickles mommy,” she said.

“I know honey but it’s bad for you ok?”

“I like it.”

Her eyes looked big and sad and I nodded.

“I know, sweetheart.”

I drank milk from then on.

When we were first dating, Jon would look at me while making love. He’d stare into my face and tell me that he wanted to swim in the blue of my eyes. I told him to jump right in. Toward the end, however, he kept his eyes shut. He’d bite his lip like he was in pain or something, but I still held him close, pressing the skin of my hands to the skin of his back till I could feel his freckles. Open your eyes, open your eyes, I’d think with each motion of his body.

The night he broke it off with me we made love again. I shouldn’t have, but he was a nostalgic person and I thought if I just had him for one more night, he’d remember what we’d meant to each other. We were on the floor with my jeans digging into my shoulder and I cried as I imagined our skin melting and sticking like glue. He wiped the tears from my cheeks, but didn’t say a word. He didn’t say a word as he gathered his clothes, as he stood in the hallway for a moment as if remembering something, or trying to forget, and he didn’t say a word when I called out his name. He just left, the click of the door handle drowning the empty house.

I’m pretty sure that was the night Elya was conceived.

I decided to homeschool her and she seemed fine with it. She liked learning about animals and plants and she loved to draw. When we finger-painted she would only use blue, so I went out and bought seven different shades of blue from three different stores. Sky blue, ocean blue, royal blue, baby blue, navy blue, denim blue, grey blue. She used all of them.

She liked being near the ocean and never really asked about other children. But the first time she saw a family swimming down the beach she would not stop pestering me to take her for a swim.

“You can’t, El, you’re allergic.”

“I’m not allergic,” she’d say.

She didn’t understand. I had to watch her from the moment she was awake to when we read stories at night. She’d sit on my lap and I’d smell her salty hair. Her favorite book was a children’s illustrated version of Moby Dick.

“You think the white whale lives in our ocean, mommy?”

“I don’t see why not,” I said.

“I want to meet him.”

I looked down at her intent little eyes. “Maybe someday he’ll come visit you.”

“But whales live in the ocean.”

“That’s right, and you live on land. Here with me.”

She nodded as she placed her small fingers on the page and stroked the picture of the giant whale.

I suppose I’d seen it coming all along. Perhaps I was even waiting for it to happen. From the moment she was born I knew she never fully belonged to me. I knew one day she’d be gone. Perhaps it was the fear of it that made me love her so much.

When I got up that night for a glass of milk I saw her through the window. She was standing on the beach in the light of the dilated moon, laughing as the waves made her toes shine like fireflies. I ran.

I could hear her giggling even as I screamed. She walked forward into the waves, laughing like she couldn’t control herself. The sand gave way under my feet as the water began to bubble and boil with a silver light that surrounded her like a dress. I yelled again, but she didn’t even turn as she sunk her head beneath a rolling black wave. Her whole body shone, white like the whale, and I could see her radiating, even from beneath the surface. It was like on nights when the moon is so bright that it burns a red and black moon-spot into your eyes and no matter where you look you see its shadow.

When I dove into the water, Elya’s shinning body was gone. I dunked under the surface and scanned the ocean, even though I couldn’t see a thing and it stung my eyes terribly.

I surfaced, my nightgown clinging to my body like a straightjacket.

“Elya.”

Nothing.

I swam and screamed and dove and searched until I fell exhausted onto the beach, staring at a night sky scarred with a few dull stars, hiding from the blinding light of the moon.

They never found a body, though I knew they wouldn’t. They searched, investigated, sent out be-on-the-lookout notices, but nothing ever turned up. Jon was devastated, or at least he pretended to be. That’s nice of him, I say to myself, that’s nice of him at least to pretend.

Sometimes I imagine her coming back, washing up on shore and shinning like a fallen star. Other times I imagine her with her whale, swimming and giggling and stroking its rough white hide. I drink a gallon of water almost every day now. And I swim. I swim every night and somehow I feel close to her when I do. I picture the water as her skin, clinging to mine. The smell of her on my face, in my hair. She gets in my eyes and it burns, but I hardly mind. Sometimes, when I’m feeling extra lonely, I dunk my head a few feet, keep my eyes closed, and fill my mouth with the salty ocean. When my cheeks are about to burst I imagine absorbing her into myself, carrying her like I did for nine months. Then I swallow, again and again until I collapse onto the shore, coughing and spitting and inhaling lungfuls of sweet, life-giving air.

Tyrell Johnson is a graduate of the MFA program at the University of California, Riverside where he studied fiction and poetry. His reviews are published at hipsterbookclub.com, his poetry can be found in the January 2011 issue of Autumn Sky Poetry, and his fiction in Pinion Journal. Sometimes he lives in Bellingham Washington, sometimes he’s in Kelowna BC with his wife Tessa and their one and a half dogs.

What do you think is the most important part of a fantasy story?

The way in which a character reacts and interacts with the magic is, for me, the essence of why we write fantasy–to put real characters with real wants and emotions in a backdrop of the fantastical. But not only should the magic do something for the story or the character, everything else around the magic must be believable and tangible, and the author must write with authority so as not to give the reader a moment to doubt. That way when readers encounter the impossible, they’ll think, since everything else is so real, why not a talking bear?