Iron Maiden

by Stefan Milicevic

In the one thousand, one hundred and first year since my creation and the twenty-second year of my incarceration, I was locked inside a class showcase, discussing the finer points of philosophy with quite the disagreeable Guillotine.

“I am simply saying that even if we are not strictly human, we possess a soul. Your insistence on an upbringing being vital does not help your case.”

Monsieur Guillotine snorted, shaking his wooden head, which at one point had been a chopping block.

“My dear, our existence is a curse. Having the ability to reason is not even beyond animals.” He gestured at me with a as much of a flourish, as the glass constraints around him allowed. The blades sprouting from his elbows clattered against the glass. “Look at yourself. If I may be blunt, I sincerely doubt that body of yours could give birth. Reproduction is a key aspect of humanity.”

I stifled a snort. It all came back to coitus with these damned Freudians. Some days I wondered if there had been an influx of perverts and pederasts in France when Monsieur Guillotine had been nothing but an instrument of torture, but I knew it had to be their literature. Hugo and Leroux, those gentlemen thrived on misery, and back in the day the quickest way to the decapitation device du jour was to write a book.

I should know, really--the inside of my lid impaled many great thinkers, many of which kept me awake at night with their tortured screams. When they were not arguing with each other.

“I’ll have you know that the Japanese have a conceit known as kami, which dictates that every object in the universe--”

“Hush, now,” Monsieur Guillotine cut me off, rather rudely. “They are coming.”

It was true, the wail of creaking stares announced that the curator was coming, but I thought it a tad too fortunate that he came down to the basement just as I was to make a rather good point.

He was not alone, however. A gangly young gentleman accompanied him, a nouveau riche if I had ever laid my eyes upon one. It was rather obvious that he came from money, and very recently at that: his motions spoke rather of raking dung than prolonged debates or scholarly reading.

“Here they are, Otto, my precious contraptions come to life,” he said, his lips curling into a smile. “Monsieur Guillotine and Fräulein Iron Maiden.”

I nodded in acknowledgment. Not that I would have curtsied, had the space inside my glass cabinet allowed it, but unlike Monsieur Guillotine I was conscious of my duty to display proper manners, even to the less fortunate members of humanity.

The boy regarded me with an innocent awe that I almost found charming.

“You were right, Uncle,” he said. “They certainly look alive. Clever engineering, indeed!”

“Excuse me?” I said. “I do not recall calling you a result of clever duties marital.” I rose my chin with a clang. “Know your place!”

The curator laughed. “Careful now, Otto. The maidy is a prickly one.”

Otto still ogled me as if I had never admonished him. “I meant no disrespect, Fräulein. By clever engineering, I meant to say that you are... beautiful.”

Such impertinence! Uninspired flattery was for pubs and houses of ill-repute, not for the Nürnberg Museum of Industrial Culture. I averted my gaze, out of sheer regard for propriety, of course.

He inspected my body from head to toe--the locks of chain and wire that sprouted from my iron-wrought skull, every jagged spike that jutted out my smooth metal body. Nothing was safe from his consideration. Had there been a heart in that hollow body of mine, its beat would have flung open the lids covering my chest.

“And no one knows how they came to life?” Otto asked, his gaze still lingering on me like a canker of rust.

The curator shrugged. “People are afraid of them. We never got a chance to examine their inner workings. I used to have more of them. Back I could still show them in the museum proper without the visitors crying bloody murder. Now I have to keep them in the basement.” He shook his head. “Such ignorance.”

The curator was right. Around me stood glass cases, hollow and forgotten. Gone were the days when I could exchange opinions with the Judas Cradle or the Brazen Bull.

“What happened to the other devices?”

“They probably got smelted.” The curator laughed. “The irony. Right now someone is sleeping on a bed that used to be a part of my torture rack.”

“Must you discuss smelting in front of us?” I bristled.

The curator raised his hand in a placating manner. “My apologies, maidy. You know you are safe with me.”

“I would love to examine them,” Otto said. “Why, I could write my thesis about it!”

The curator ruffled the boy’s hair. “Easy, boy. You have five semesters to go. Can I count on your assistance over the next month?”

“Of course, uncle.”

I cleared my throat, eliciting the sound of a nail being dragged across an iron sheet. “Come again, sir?”

The curator put a hand on Otto’s shoulder. “Otto will be doing maintenance on you. He is an engineering student with the University of Berlin and I decided to help him for his trouble. A couple of marks for every hour he spends with you two--cleaning, polishing, oiling-- the whole works.”

His words hurt like ulcers of corrosion. Our own curator relegating his duty to a plebeian to save a couple of marks. I would have to consult one of the voices in my head to see if there was a circle in hell reserved for tightfisted old men.

The two men excused themselves, leaving me once again in the questionable company of Monsieur Guillotine.

“Young Otto is quite smitten with you,” he said.

I scoffed. “Now I have it on good authority that they used you to behead writers, dear.”

“Can you blame the fool?” he said, his voice laden with poisonous sarcasm. “You are a rose without petals.”

The plebeian thought that he could he win me over with books. One week after committing to his maintenance duties he made it a point to lug tomes of philosophy and history to the basement, which much to his dismay failed to capture my fancy.

Otto knit his eyebrows, two curious caterpillars wriggling on his forehead. Despicable.

“Uncle said you love books,” he said.

“I do. However, I never said it was your duty to furnish me with reading material, young man.”

“Banish the thought, boy. Her head is filled with nonsense as it is.”

“I appreciate it when you keep your opinions to yourself, Monsieur Guillotine.”

“Quiet, you two,” Otto said. He inspected the leather-bound tome. The title read Poetica. Grecian reading. Enough to pique my interest, but I had my doubts about the plebeian’s competence to argue with me on an intellectual level. Oh, he could read, but life would be very dull if a debate consisted of nothing more than parroting other great thinkers.

“Your reticence baffles me. My colleagues recommended these.”

“Oh, did they?” I cursed the fact that my body was not as pliable as I wished. I would have crinkled my nose otherwise. “I recommend you read some of these yourself before you wish to match wits with me.” I pointed at the heap of books outside my glass prison--books by Diogenes, Hobbs, Schiller and Goethe, coated in dust.

“Bribery will not bring you far, young man.”

“But I need to help you. Uncle has been clear about it and you need it too.”

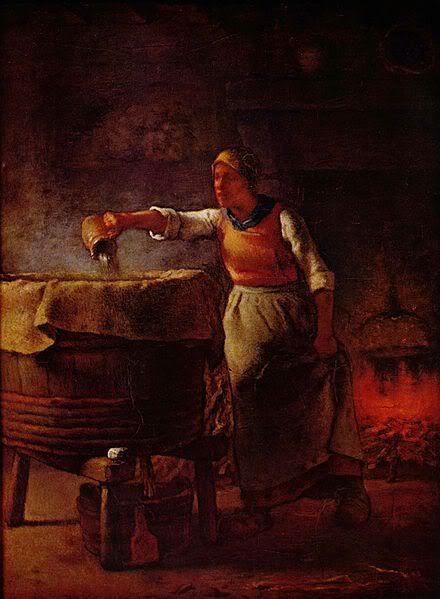

He was right. Lichenous patches of rust crusted some of my surfaces and each movement brought forth a chorus of creaks. Never mind how dust managed to sneak and creep into crevasses, drying my joints. Even moving in my glass cage caused friction that induced gangrenous pain.

But my resolve remained unshaken. I was a woman of principle.

“Just let me oil and varnish you.”

“Never.”

The boy threw the book onto the ever growing heap in the corner. Such disregard for literature.

“Fine. If I prove myself your equal, you shall let me do my duty.”

Monsieur Guillotine chuckled, the sound of a butcher’s knife hitting hardwood.

“Do your worst, boy,” I replied. “You threw down the gauntlet, so the topic of discourse shall be of my choosing.”

“Very well.”

I had a topic in mind the moment he spoke. I harbored no hope of him actually elucidating me, but it was a hobbyhorse of mine.

“What does it mean to be human?”

Otto laughed. “I am engineer. Do you think I concern myself with humanity?”

I twirled a lock of chain around my finger, offering him the slightest of smiles. “You are a boy who got sent to University thanks to his Father’s hefty bursary. Engineer or not, do you accept this challenge?”

His pained grimace made my inner workings jingle and jangle. How I derived such pleasure from seeing him squirm I did not know, but the base enjoyment of playful banter made me feel alive. I suppose the boy was to be commended--his mere presence spurred my curiosity about humanity.

“All right.” Otto took a moment to concentrate. The sight of him fidgeting in his cheap finery was quite lovely.

“Being human is about knowing about love, I suppose.”

“Ever the plebeian!”

“What is your counter-argument?”

I swiftly consulted the plethora of thinkers roaming within me. Their spirits clashed like swords, metal ringing on metal, each sound an opinion, a school of thought. As was their habit, their dissent erupted into a skull-cracking headache. I shooed the voices into compliance and siphoned an assortment of attractive ideologies, a varied enough arsenal to hold my own against Otto.

“Well, according to--”

Otto made a cutting motion with his palm. “None of that. I want to know what you think, not what you read.”

“Read?” I said, feeling as if my head had been dipped into a smelting oven. “Countless thinkers have died by hand. You dare to question the quality of my victims?”

“Really?” Otto scratched the fern that was his beard. There was a flash in his eyes, a lovely glitter of curiosity. “Uncle mentioned something to that effect. The memories of the dead stay with you. What mechanism within you could possibly account for that?”

The dead. The memories. It all came back to me, memories leaking through my once well-maintained mental dam. The screams and the keening of entire families, maidens, mothers and crones. With the memories came the clitter-clatters. My limbs creaked and convulsed. My knee joints collapsed and I sagged against the glass wall.

Otto flung open the door and cradled me in his arms, my spikes piercing skin and impaling flesh.

“Maidy? What happened? God in heaven, you need maintenance.”

“Do not ever mention them,” I said, my voice rusty.

“Pardon?”

“The deaths. They bring the clitter-clatters.”

“Oh. I understand,” he said through gritted teeth, in a way that indicated that he did not understand at all.

“You are bleeding.”

“That means I win our little battle of wits, does it not? Bleeding for love makes us human.”

“Hah, he got you there, maidy,” Monsieur Guillotine said, as if what transpired before him had been nothing but a play.

“Please,” Otto said, “let me perform a routine maintenance on you.”

And he did. After bandaging his wounds, he oiled and varnished me. An unfamiliar sensation rose inside me and my inner voices informed me that it was shame.

But also pleasure.

As the days went by, Otto spent time with me beyond his scheduled maintenance duties dictated. Our banter became more intimate and after a little while, we started to disregard Monsieur Guillotine’s presence altogether. At least he had the manners to feign being in torpor.

Our curious exchanges were centered on us. Our lives and dreams. I had little to relate-- I had no memories to speak of, not before I became assumed a humanoid shape and became conscious. My other memories were unpleasant at best--Luddite witch hunts, stoning, and promises of hot furnaces and melting pots.

“It is unfortunate that people are so bigoted,” Otto said wistfully. “There is so much we could learn from you. You are marvelous--a machine turned human. Marvelous, I tell you.”

He had a way of making me feel hot and bothered. The philosopher and educator in me wanted to reprimand him for his wanton behavior, but the pleasure of hearing him praise me outweighed all the voices in my head.

That must be love, I mused to myself. Casting aside common sense even if one should know better.

“I would love to introduce you to my colleagues. They would be astonished if they could see you.”

The gift made me fall for him completely. Lest someone decry me as a materialist, it was the intention that made me consider him more than a mere flirt.

“Is there anything human that you desire?”

“Something tangible,” I said. “A chemise.”

He laughed. “I did not take you for a woman of fashion.”

“Why not? I have a great mind, if I may say so myself. I want something to own.”

“A chemise does not make a woman.”

“A chemise makes a charming woman, love.”

Sure enough, one week later, in a show of astounding imagination, he brought me a lovely magenta chemise.

“I had the clothier take your spikes into account,” he said as I was slipping it on.

It was true--it fit, for the lack of a better metaphor, like a glove. Each spike had its own pocket and the cloth was sturdy enough that it didn’t rip.

“Why so silent?” Otto asked me.

Curses. He noticed my trepidation. “I just noticed that all the time I had been naked in front of you.”

It had been a month before Monsieur Guillotine asked a most bewildering question.

“Say, Iron Maiden, who is that young man?”

“Surely you jest,” I said, thinking his question just another ill-advised attempt to ridicule me.

“Honestly, I do not remember being introduced to him. I did not want to interrupt you two, so that is why I am asking now.”

“Read up on Wilde. Your sense of humor is stale. He is the curator’s nephew.”

“Which curator?”

Little did I know that Monsieur Guillotine’s joke would prove prophetic.

They came at night. One swift stroke of the clothier’s hammer shattered my glass case and they dragged me out, ever so mindful of my spikes.

“We’ve got you now, slag,” the clothier said. I remembered him from Otto’s description--grandfatherly face, a puff of hair clinging to his balding pate. “Prepare yourself. The smith has need of new nails. The furnace will be your hell.”

“Let me go,” I cried. “I am like you! I can reason! I can love!”

The hammer came down with a sickening clang. For an instant my world became a blur, the inside of my head resounding with an irritating ring.

The clothier’s cohorts guffawed as if I had just told a bawdy joke.

“A woman’s face don’t bend like that.”

The clothier and his rogues brought a chest with them. I thrashed, I writhed, I screamed and I bled them to no avail. They stuffed me into the chest with little effort. Monsieur Guillotine, I noticed before they shut the lid, was limp like a rag doll, slouching against his glass showcase.

The clothier ripped the chemise from my body, shaking the fistful of cloth angrily at me.

“The likes of you need no nice clothes.”

They shut the lid and the clasp snapped closed with eerie finality.

I could still hear them in the darkness, the sound of their voices dampened, but vicious nonetheless.

“What do we do with the guillotine?”

“Leave him be,” said the clothier. “He ran his course, I reckon.”

I did not know where they were taking me. In the darkness I could do nothing but consult the voices in my head, hoping against hope that I could piece together a compelling argument; an argument that would appeal to the humanity in my captors. My voices proved not as charitable as I had hoped. My thoughts felt palsied and rotten.

Pieces of discourse and ideology slipped away from me as if run through a sieve. Information frayed, knowledge paled.

Panic seized me and no amount of reason could help me now. I decided to calm myself, composing essays and dissertations in my mind, but no single sentence stayed coherent.

I forgot. I forgot too much. Just like Monsieur Guillotine. I wondered how long it would take for me to regress into a tool of murder. A facsimile of a murderous doll.

Minutes felt like hours, and the hours stretched into infinity. I jounced left and right, denting with each bump. I needed maintenance. I needed safety.

But no one was there.

My vocabulary shriveled. Before long I kept time by the number of things I forgot.

I never forgot Otto, though. I retained enough working knowledge of fairy tale narrative and Jung’s collective unconscious that I sussed the pattern of events to come.

At least I thought I did.

Untold days later a crowbar slid into the tiny gap between the lid and the chest’s body.

Light, lovely light flooded into my dark little world and like an angel haloed by its glow was Otto. My Otto.

I wanted to pounce at him, but did not, out of fear of injuring him.

“This was not what I had in mind when I said I wanted to introduce you to my colleagues,” he said hastily.

“What do you mean?”

“The clothier put them up to it, damn him. Look, think of it as a practical joke on their part.”

I looked around me. Furnaces and melting pots surrounded us. A plethora of steel tools hung on the walls--hammers, pliers, and tongs.

“A practical joke?” I said, my voice gritty. I needed oil. More importantly, I needed an explanation. “Look at what they’ve done to me.” I was battered and tarnished. While I had lost a good portion of my education, I still had a firm grasp of practical jokes. “They want to smelt me. Your colleagues want to murder me.”

Otto put up his hand, as if they could shield him from me. “They should know better! They are tomorrow’s engineers, for God’s sake. Give them time and they will understand. Once we dismantle you and find a way to harness your inner secrets, you will finally have a purpose again.”

I forgot most of my Aristotle. Freud and Jung slipped away. But what I most wanted to forget was what Otto had dared to utter next.

“Think about it, you will no longer be a tool of murder. After we put your inner workings to good use, you shall forever be a part of humanity. You shall be cherished. Is that not marvelous?”

I wished for a wind of rust and decay to wash over my body.

“See? I brought my tool box.” He lifted it as if showing it to a dolt. “We must hurry, and yes I am still an apprentice engineer, but I love a challenge. Remember, I bested you at your own game.” He laughed.

I wished for well-oiled hinges that connected sharp blades.

“Now if you let me dismantle you now, I shall be able to sketch out a blueprint for each part of your body. Think of all the advancements we could claim for our own! Prosthetics, complex machinery, nay, intelligent machinery! The list is endless.”

I wished for blood and screams.

And yet I still loved him.

The clitter-clatters returned and with them a sobering realization. Otto was right. To be human means to love and have a purpose. It was the missing piece of the puzzle, the Marx to my Engels. How foolish had I been--I almost travelled down the path of obsolescence, much like my friend the guillotine.

I thrust my arm out and impaled Otto.

His scream was a symphony, waking hidden desires in me. I finally understood, I finally had found my purpose, the very reason of my existence.

As the blood left his body, I frantically searched for his voice inside my head, like a gambler rifling through a deck of cards.

I found him screaming into the abyss of my conscious. It was all well, though. Pain was humanity. Purpose was humanity. Loss was humanity. I would never forget about him. About his kindness, about the Otto that he once had been. I still had a lot to learn, but as long as I could retain my memories there, I could bide my time. I heard the clothier and his cohorts approach. I just stood there. Waiting. Blood smeared my body and the tatters of my chemise snapped like banners with my every move.

Let them come.

I would love them all.

Stefan Milicevic is an author of fantasy, horror and science fiction who likes to talk about himself in third person (which makes him sound kind of important). When he is not involved in a mind-racking game of Go or Shogi, you can find him tinkering with a new story, or hanging out with his friends. He is also fluent in four languages and can't waltz to save his life.

What do you think is the attraction of the fantasy genre?

The sheer possibilities and depth of the subject matter. Well-written fantasy stories are a crucial part of the modern myth.