by Kara Lee

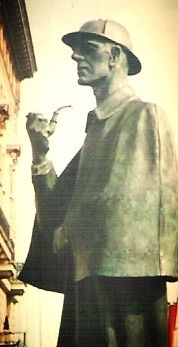

In the great city of London, on the busy thoroughfare called Baker Street, atop a stone pedestal, facing the dilapidated flat of 221B, stood a bronze statue of a man. An Inverness cape draped over his shoulders, a deerstalker cap sat on his head, and in one hand he held a pipe.

Every day, thousands of Londoners walked past this statue, neither knowing nor caring who the man had been. Only curious children stopped sometimes to inspect the plaque below his feet, whose eroded letters barely formed the words:

1854-1881

Above the worn plaque was a fresh broadsheet, proclaiming that the statue had been condemned to be demolished by the new year, for the property it stood upon had fallen into financial arrears.

One day, just past Christmas, a swallow like thousands of other swallows flew over Baker Street. He was hungry, for there were few insects to eat during London winters. An old woman had tossed a handful of breadcrumbs at the pigeons in Regent's Park, but they would not share their precious food with the swallow. And so when the swallow noticed that a number of grains were scattered on the pavement in front of the statue, he swooped down and happily took a seed into his beak.

"I would not eat that if I were you," spoke the Statue, "for were I still alive, I should wager my life on it being poisoned."

The Swallow dropped the seed in alarm, and flew up to greet his savior. "How could you tell?"

"For what other purpose," said the Statue, "are seeds scattered on the pavement in winter? I am afraid you overestimate the kindness of men, Swallow."

"Ah, but you have been kind to me," said the Swallow as he perched upon the metallic shoulder. "Who are you?"

"I am the Great Detective, Sherlock Holmes," answered the Statue. "In life, I solved hundreds of Scotland Yard's most difficult cases, but I am forgotten now."

"Indeed, for I have never heard of you," returned the Swallow.

"As London does not know my name," said Sherlock Holmes, "I would have been surprised had it reached all the way to Afghanistan, where you once had a dear friend--a doctor, if I am not mistaken. My condolences on your loss, Swallow."

"How could you possibly have known?" cried the Swallow in astonishment.

"It is the simplest of reasoning," said the Statue. "You have a blue bead tied around your right leg with a cord of leather; surely a human's doing. The knot is a surgical one; surely a physician's work. The bead is lapis lazuli, of a superb color and quality characteristic of Afghanistan, where swallows winter; only a very dear friend there would give you such a gift. And although it is December, you do not make haste to return to his side; therefore he must have already passed from this world."

"Your methods are astounding!" said the Swallow. "Indeed, I was the companion of a British surgeon named John Watson, whom I met in the bloody fields of Afghanistan. Sadly, he died of enteric fever in a London hospital only yesterday. That is why I am late to migrate for the winter, you see, as I could not let a dear friend die alone. Truly, Statue, you are brilliant. It is a loss to the world that you and your works are forgotten."

"Then, Swallow," said the Statue, "will you not help me be remembered once again?"

"How do you mean?" said the Swallow.

"There was one last mystery that I could not solve before my death. And I cannot solve it now, for I am frozen to this spot. But you are free to fly throughout London. Will you not assist me in untangling this mystery, and once more demonstrate my methods to the world?"

"No, for I must fly south tonight," answered the Swallow. "I have tarried too long; London is cold, and I have nothing to eat. I must be on my way to wintering in Afghanistan."

"But my dear Swallow," said the Statue, "a man was killed. Will you not help me to ensure that justice is served?"

And the Swallow was moved.

"Very well," he answered. "I shall stay for one night. What do you need me to do?"

"There was an Inspector Lestrade, with whom I worked during my lifetime. He has since died, but according to the police blotters that Londoners so often discard at my feet, his son--Constable Lestrade--takes after him in every way. You shall request aid from the young Constable."

"How, Statue?"

"I shall give you the location of a secret office once used by my late brother, Mycroft Holmes. I believe a Swallow is just the right size for a telegraph key--thus you may send my telegrams for me."

"The Constable may think your messages are jests."

"Not to worry, for by my signature he shall know me."

"I will do as you ask," said the Swallow, "But Statue, as you are so intelligent, I have a mystery for you. When I flew through Belgravia this morning, I saw a woman in distress, for her sister was traveling with a number of jewels, and both have disappeared. Please, Statue, lend her your aid."

"Missing women and stolen jewels are pennies to the dozen," complained the Statue. "Solving that would be a waste of both my time and my talent."

"Why then," said the Swallow, "are you admitting that there are mysteries you cannot solve?"

"That is not what I said," protested the Statue. "Oh, very well. Tell me the details of her case, and I shall no doubt be able to solve it."

That evening, an overjoyed Lady Florence Calvert was reunited with her beloved sister. Clutched in one gloved hand, as precious as the recovered pearls and diamonds, was a mysterious telegram from an S.H.

Shortly thereafter, another message was delivered to Scotland Yard:

FOR CONSTABLE LESTRADES EYES ONLY STOP THIS IS THE GHOST OF SHERLOCK HOLMES I HAVE RETURNED TO SOLVE MY STUDY IN SCARLET STOP COME TO MY STATUE AT MIDNIGHT STOP INCIDENTALLY AS TO YOUR CASE OF THE SURREY WEREWOLF THE CIGAR SMOKER IS THE MURDERER STOP

Constable Lestrade showed up that night, trudging through a cold falling rain. He stared up at the statue with bloodshot eyes. The Swallow hid, shivering, under a bronzed flap of the Statue's cape.

"My father always did say you were a pain in the arse," the Constable said, "and it seems even death can't stop you in that regard. Still, I came because you solved that case in Surrey--I'd make a deal with the Devil Himself if it'd keep rippers off the streets." He fished a notepad out of a coat pocket. "My father wrote up this case himself. I'll read it to you, for all the good it does now, so many years on.

"'It was a nasty business out in Brixton that night. The constable on his beat had found a murdered man at about two in the morning. We asked Holmes for help, but Holmes said, to quote, that he could "solve this study in scarlet faster than all Scotland Yard combined", and shut the door in our faces. That was the last we saw of him.

"'We followed the constable to an empty house in Lauriston Gardens. Inside was a dead man, covered in blood, but unwounded. On the body we found a card-case identifying him as Enoch J. Drebbler, and a note scribbled with the name of Joseph Stangerson. In a corner of the house, we found a woman's wedding-band. Finally, on a wall, we saw the word RACHE scrawled in blood (we later posted advertisements for a ring belonging to a Rachel, but no-one ever came forward).

"'Also the next morning, we found Drebbler's landlady, who gave us Stangerson's description and an address at Halliday's Private Hotel. But the wretch had checked out by the time we arrived, and we never did find him. He must have been Drebbler's murderer, or why else should he escape? Much as I resent Sherlock Holmes--a more arrogant bastard never lived--I am not too proud to admit that if only he had helped us, we would have caught our man.'"

"Poor Inspector Lestrade," Sherlock Holmes murmured after the Constable had quit the scene. "He never learned my methods. What a shame."

"Were there no clues?"

"There were many, but misinterpreted. For instance, Rache is the German for revenge, my dear Swallow. That, along with the wedding-ring, tells us that the motives for the crime were love and retribution."

"It is a shame you were not there to help at the time, Statue."

"Perhaps, but the case is not hopeless even now. The Constable must continue where his father left off in the search for Stangerson. Will you not send him another message, Swallow?"

"Tonight I am bound for Afghanistan," answered the Swallow. "London is gray and dreary, as are its people. I long for green hills and flower-meadows, and children who fly the most beautiful kites."

"But Swallow," said the Statue, "if only you could stay one more night, we might find where Stangerson has escaped."

"Very well," said the Swallow, "I shall stay one more night."

"Then, please send a telegram advising the Constable to search Scotland Yard's records for other crimes at or near Halliday's. Advise him to tell no-one of what he finds, lest we prematurely alert the murderer. And please add that in the matter of the twisted staircase, he is to look for a red rooftop, where he will find all he needs."

"I will do so," said the Swallow. "But first, may I bring another mystery to your attention? Today, when I flew over Shoreditch, I found an artist of small ceramic miniatures, who has found his warehouse ransacked. Will you not help him?"

Bronze eyes cannot roll, but the Swallow fancied that Sherlock Holmes made a valiant effort at it.

"Yes, if I must," the Statue said with a sigh.

The next morning, an overjoyed artist found not only his missing statuettes, but also an enormous star sapphire hidden inside one of his works. He locked up his wares carefully, along with a telegram from S.H.

Constable Lestrade came to the statue again at the next midnight, which was even colder than the previous. But he barely appeared to notice the weather, so excited was he at having solved a second case that had puzzled Scotland Yard for the past week.

After giving his profuse thanks, the young man revealed that his inquiries had borne fruit. Indeed, a month after Stangerson vacated his room, a maid had reported a strange theft.

There was a storage room on the topmost floor of the hotel, where she had gone for linens. But instead of sheets, the girl had found splatters of dried blood on the floor, a broken window, and a bloody chair. Scotland Yard had dutifully recorded the robbery, but finding no clues, never pursued the case.

"That must have been Stangerson," Constable Lestrade said, brows furrowed as if in deep thought. "I'd guess he heard the police coming. He escaped to the storage room, made a ladder out of linens, smashed a window with a chair, and escaped. The glass cut him on his way out. That explains everything. If only my old man had discovered this!"

But when the Constable had left, the Statue chuckled.

"He grasps at straws," he remarked, "while letting gems fall through his fingers."

"It all sounded quite plausible to me, Statue."

"Consider," said Sherlock Holmes, "if Stangerson broke a window to escape, his blood would be more outside than in. No; the glass was shattered after the blood had been spilt, likely when Stangerson struck a second person in the room with the chair."

"A second person, Statue?"

"Indeed: Drebbler's killer, who had come for Stangerson."

"I do not see how you know that it was Drebbler's killer, not Stangerson himself, who died in that room."

"My dear Swallow, Drebbler's killer left the corpse for all to find, but this killer hid the bodies. Different methods suggest different murderers, therefore, it must have been Stangerson."

"How do you know that murder was committed?"

"Had Lestrade been familiar with that hotel, he would know there are rope ladders readily available from all the floors; no linens would have been needed for an escape. Therefore their only use to a murderer would have been to wrap a dead body. You must inform Constable Lestrade of this to-night."

"I saw frostflowers in many windows this morning," answered the Swallow. "I must fly south now, where the windowpanes are open to receive the warm breeze."

"Swallow, Swallow," cried the Statue. "I only need one more night to find the murder victim. You cannot leave me now!"

"Very well, I will stay one last night," said the Swallow. "How do you propose to find the body?"

"Why, Stangerson must have disposed of it. He had no tools with which to dig, thus he could only have used an abandoned building. Moreover, he can hardly have gone very far, for a human body is a heavy burden in every sense. Therefore our Constable ought to search buildings near Halliday's Private Hotel that have remained abandoned for all these years. You will follow him, and report all to me."

"I shall do so," answered the Swallow. "But first, I must ask--"

"Yes, yes, tell me what trivial puzzle you want solved this time," interrupted the Statue with a put-upon sigh, "so that we may get on with my far more interesting mystery."

And the Swallow did.

That night, a young clerk at a wealthy shipping firm in Canary Wharf led Scotland Yard to a banker who had embezzled vast amounts of funds. When asked how he had discovered this, the clerk could only hold up a mysterious telegram from an S.H.

The next day the Swallow followed Constable Lestrade. It was a cold day, far too chilled for his thin coat of feathers, but he warmed himself with the knowledge that he should soon be flying south.

First thing in the morning, the Constable went to a records office to compile a list of houses, factories, and shops within the vicinity of the Hotel that had remained empty from the time of Drebbler's murder until the present day. He investigated all his entries, braving muck, rubbish, and worse. But these efforts turned up nothing. Constable Lestrade returned to the office in the afternoon, face red and voice frantic, to ask whether he had missed any buildings.

"Well, I suppose there's a factory that was just sold last week," answered a clerk. "The building's soaked through with poison from metalworking. You couldn't pay anyone enough money to deal with it, that's why it's sat empty for twenty-some years. Yet a speculator bought it for a stupendous sum, and I understand he's to demolish it. Demolishing money's all he'll be doing, if you ask me."

Constable Lestrade fairly tore out of the office to the factory in question. It was an ugly box of soot-stained brick. Constable Lestrade managed to pick his way in through a broken plate-glass window, and the Swallow followed.

Inside, rubbish and chemical odors filled up the abandoned factory. Broken wood slats, scrap metal, rusted industrial machines, and smashed glass were piled on the floor. At the bottom of the mound, peeking out, were the edges of what had once been white linens.

Constable Lestrade put on a pair of sturdy gloves and very carefully cleared the debris off the linens. His efforts soon revealed a heavy cloth bundle, which was stained through in parts with the black of old dried blood. He unwrapped the fabric to find the decayed corpse of a tall man, wearing a brown overcoat. A crushed skull indicated how he had died. "Perhaps it was the chair that did him in," the Constable murmured.

On the corpse was a cab-license identifying the man as Jefferson Hope. But of far more interest to the Constable was a diary, in which Hope had recorded his furious hatred for Drebbler and Stangerson. For they had destroyed Lucy Ferrier, the love of Jefferson Hope's life and the erstwhile owner of the found ring. Stangerson had killed Lucy's father, John Ferris, after which Drebbler forced the girl into marrying himself. The two shocks had soon killed her. Hope's very last entry described how he tracked down and killed Drebbler--and planned next to kill Stangerson.

"I've done it!" Constable Lestrade cried out as he closed the fragile diary with shaking hands. "I've solved a twenty-year old cold case! My name will be made, and my promotion is ensured--halloa, what's this?"

For he had just noticed that there was yet more linen under the debris. Constable Lestrade went back to the rubbish-heap and pulled the fabric out, only to find that these cloths were wrapped around a second bloody bundle. He unwrapped the linens and gave a gasp of shock.

The body might have been too long dead and the visage too crushed to identify, but there was no mistaking the heavy cape, the tobacco-pipe tucked into a pocket, and the deerstalker cap.

It was the corpse of Sherlock Holmes.

"This is what happened that night, to the best of my knowledge," said the Statue of Sherlock Holmes, when the Swallow returned with the discovery.

"Scotland Yard came to me for help. I was too proud to acquiesce, for I had done so before, hundreds of times, and without fail, Lestrade and his lot captured all the credit. So instead, I resolved to solve their case before they could, and expose them as the incompetents they were.

"I beat them to the crime scene and performed my inspection. I knew immediately that Stangerson was the next intended victim. I decided to search for him, as it would be the fastest way to find the murderer.

"I traced Stangerson to Halliday's. I surveyed the hotel, and resolved to wait for the murderer in the storage room, as it was on the topmost floor, and had an excellent view of the street. I snuck in via a rope-ladder. But the moment that I entered, something smashed into my head, and I knew nothing more."

"So the murderer killed you, then, Statue?"

"Which murderer, Swallow?"

"Why, Drebbler's, of course."

"Indeed not. The storage room was quite far from Stangeron's room. A murderer would remain near his intended victim. In contrast, a target--Stangerson--would hide away as I did. But in this case, the hunted was just as brutal as the hunter: Stangerson ambushed and killed me."

"But why, Statue?"

"A mistake. Understandable. When I snuck into the room, he thought I was his pursuer, for who else would sneak into his hotel but Jefferson Hope? And so he attacked and killed me. Later that night, Hope arrived, and Stangerson killed him as well. Then Stangerson fled, dumping both bodies. Case closed, I am afraid. What a disappointment!"

"How so?" said the Swallow, confused. "Hope, Drebbler's murderer, is dead. But we need to pursue Stangerson, for he killed you both!"

"We have no such need," said the Statue. "I only asked that you remain with me to help solve my last case. That has now been achieved. Fly south, Swallow, before you suffer overmuch from London's winter."

For indeed it was quite cold now. Children came and went with skates tied in bundles, their cheeks rosy and their breath hanging in the air. The rich went about in wools and furs, while the poor shivered along with the swallow.

"You do not wish my help in finding your own killer, Statue?"

"Why should I? My death is utterly uninteresting. Nothing more than a by-product of my own shoddy work, of being off my guard. What sort of great detective am I, to have been killed by a common criminal? I am nothing at all, Swallow, just another murder victim on the streets of London. My death is not worth solving."

"How can you think thus?" cried the Swallow. "All lives are important."

"Mine was not," said the Statue. "As you can see, Scotland Yard does not remember my works. My only family was my elder brother, who died of a shock to the heart upon my death. I had no colleagues to miss me, no friends to mourn me."

"But at least you must have had someone," said the Swallow, "who put up your statue."

"Ah," said Sherlock Holmes. "There was an obscure writer named Arthur Conan Doyle, who came across one of my monographs on the science of deduction. But he was neither friend nor colleague; rather, he was my admirer. He wrote up a number of my cases for publication, but they did not become popular with the readers or the critics. After my death, he spent the remainder of his funds on purchasing my flat, and erecting my statue. But now that he is dead, there is no one left to care what becomes of me."

He said it all dispassionately, with an absolute coldness surpassing that of the winter around them.

"You are wrong," said the Swallow, "for I care. And I shall not leave London until I bring your killer to justice."

And the Statue was silent, but the Swallow thought that the metal trembled very slightly. Then again, it might have been from the wind, for a fierce northern gale began to besiege London that very night.

"Now how might we find Stangerson, Statue?" asked the bird. "For he may be in London, or America, or the Antarctic for all we know. Worse yet, he may already be dead, and past the reach of justice."

"Stangerson," returned the Statue, "is alive and currently in London, where he will likely remain for a small while, but not much longer."

"How in the world," cried the Swallow, "could you possibly know that?"

"Why, you yourself heard from the Constable that a speculator had bought that lot. The clerk considered the purchase bizarre, because he failed to consider whom such an action would benefit. The answer is obvious! Stangerson is the speculator, who seeks to demolish the building in order to destroy all evidence of his murders. To him, this would be worth any sum."

"Then we must find and stop him, immediately! Shall I inform the Constable?"

"No, he is only one man, which is far too slow for our purposes. Instead I shall make use of my old street network, the Baker Street Irregulars. Some of them may remember me--but even if not, they will likely do as they are asked, if a coin is dropped into the bargain. In three days, I am certain, they can cover every real estate firm in London and find the purchaser. I have a small cache of coins hidden in my old flat. In the morning, you shall fetch some shillings, and send my instructions for me."

But at the next dawn, two rough-looking men came up to the Statue. They wore the sturdy clothing of day-laborers and gave the bronze detective appraising glances.

"Is this the one?" said one, a shovel over his shoulder.

"Seems like," said the other. "Awful ugly bloke, ain't he? London'll be less one eyesore once he's taken down. Tomorrow morning it is, then."

When the men had left, the Swallow fluttered about in horror.

"They're going to tear you down before your network can find Stangerson!" he cried. "We must do something!"

"I am afraid," said the Statue, "that we have come to something I cannot defeat or outthink. I have enough funds to pay my network, but not to buy an entire plot of land in central London. There is nothing I can do, Swallow."

And then the Swallow said, "No, but there is something that I can do."

The Statue said, in disbelief, "How can you possibly save me, Swallow?"

"I cannot," answered the Swallow. "But those who care about you will."

So saying, the bird flew off to the telegram office, where he worked through the night. He sent three new telegrams to the people whom the Statue had helped. He sent a telegram to Constable Lestrade. Then he sent telegrams to every newspaper in London, informing them that the ghost of Sherlock Holmes, the greatest detective the world had never known, had returned to London and was solving crimes--and that he had once lived at 221B Baker Street, which was about to be demolished.

In the morning, London was in an uproar. Newspapers everywhere shrieked of the ghostly detective. Scotland Yard, and Constable Lestrade, were mobbed by members of the public who had never cared for Sherlock Holmes in his life, but found his spirit absolutely fascinating. And of course, the clients whom Sherlock Holmes had helped went to every newspaper to confirm, retell, and embellish their own ghostly stories. Even the more skeptical Londoners were fascinated, for it was an entertaining tale, whether or not it was true. People surrounded the statue and the flat, protesting in the streets at the thought of a crime-solving ghost-detective being demolished.

By noon, an enormous throng had gathered at 221B, trying to catch a glimpse of the suddenly-celebrated flat. Enterprising publishers managed to find previously unsold copies of Doyle's stories, which now sold like hotcakes. The Lord Mayor's office bowed to this deluge of publicity, and decided to delay the demolishing of the statue until people stopped paying it attention.

For three days, even as temperatures plummeted and snowflakes fell, the public remained, preventing the statue from being demolished. And for three days, the Swallow dropped shillings and instructions into the hands of the Irregulars.

On the third day, a former street urchin named Wiggins found Stangerson working as a minor clerk in a bank. He reported Stangerson's address, workplace, and schedule to the Statue. Moreover, Wiggins reported, Stangerson had recently purchased a large quantity of concrete, whose purpose was only too clear.

"We must stop him," said the Swallow.

"And so we shall," said the detective. "But after that, my dear swallow, you must fly south for the winter, for London shall soon become intolerably cold."

Indeed, the snow had stopped falling upon the city, and had crystallized into a thin sheet of silvery glittering frost.

"Tell me what I must do," said the Swallow.

"If you would, please send Stangerson a telegram, asking him to come to this very spot in order to discuss some old residents of his new property. And of course, you shall send our Constable a message as well."

That night, a final telegram landed on Constable Lestrade's desk.

THIS IS THE GHOST OF SHERLOCK HOLMES STOP MY MURDERER WILL BE AT 221B TONIGHT STOP

Stangerson arrived at midnight, his breath coming out in white puffs. He stood before the statue, as the message had requested, and he stamped his feet and shivered and cursed, hands inside his pockets.

"What sort of ruse is this?" Stangerson hissed at the statue, which remained silent and still under the snow. He did not notice a swallow, perched on the bronze shoulder. "I know you're dead. I killed the both of you, and my only regret is not shooting that cabbie when I shot that girl's father all those years ago. Would've saved me untold trouble! Anyway, it's too late for ghostly tricks now. After I bury your bodies for good, I'll go back to America, and start over at last."

"You shall not!" cried the voice of Constable Lestrade as he stepped out of the shadows. "You are under arrest for the murders of John Ferrier, Jefferson Hope, and Sherlock Holmes."

In one swift movement, Stangerson pulled a gun out of his pocket and fired. Constable Lestrade collapsed to the ground, blood spurting from his right leg.

The Swallow flew towards Stangerson and with all his might, pecked at Stangerson's eyes. Caught off guard, Stangerson screamed and dropped the gun, then turned to run from the assault by the furious bird. But he was blinded and the ground was icy, and so he slipped and went flying straight into the statue of Sherlock Holmes.

Joseph Stangerson dropped like a stone.

Constable Lestrade, sensibly, had planned for backup. Less sensibly, he had arrived early and alone. Nevertheless, within a minute, other constables on the beat arrived, having heard the gunshot. Constable Lestrade, through teeth gritted in pain, recounted the entire case to the other men as they called for a stretcher and a wagon, and carted him away into a hospital. Stangerson was also carried away, in cuffs.

"How brilliant you were tonight!" said the Swallow, after all the police had left. "Only I suppose the Constable shall get the credit. Even if the public believes in ghosts, Scotland Yard does not. I am sorry that this will not bring you the recognition you wished for."

"To the contrary," said the Statue, "I have been lauded for the past three days by an adoring public. It is strange, but I find that I do not care for recognition as much as I had thought. Rather, I only cared for the mystery, and your help in my solving it."

"My help, Statue?"

"Indeed," said the Statue. "You were, if I might say so, in the nature of a partner to me on this case."

"I am so happy," said the Swallow, "that you feel this way." It was quite cold, but he had stopped shivering some time ago. He supposed it was the praise warming him. "And now that your murderer has met justice, I can finally be on my way. But although I dearly miss the warm winds of the south, I wish that I could remain here with you."

"I see no reason you cannot," said the Statue. "A singular advantage of London is its many criminals. I am sure that another case will arrive before long. If you like, we can work together again. What do you say that that, my dear Swallow?"

"I should like nothing more," said the Swallow, and then it was as if he fell asleep. He dropped from the Statue's shoulder into the shimmering frost at its feet, and he did not move again.

By morning, the news of how the ghost of Sherlock Holmes had solved his own murder mystery, and even knocked out his own killer, had broken all over London.

The Sherlock Holmes mania seized the public harder than ever before. Some newspapers quipped that Sherlock Holmes must be the greatest detective in both this world and the next. Other, wilder stories circulated that Sherlock Holmes had never died, had indeed faked his own death.

The statue and the flat were handed over to a newly created Trust for their refurbishment and maintenance. This Trust hired a metallurgist to survey the condition of the statue. He found that it was in excellent condition, save for a crack deep inside its chest--exactly where the heart would be, if the statue were a living man. In his report, the metallurgist attributed the fracture to the weather, for there had been a severe cold snap the night before.

In all the excitement, no one noticed a dead swallow at the foot of the statue, except a rubbish-man making his rounds. He shook his head sadly when he saw the feathered body, frozen stiff.

"Poor creature. Why didn't you fly south, you foolish thing?"

So saying, he swept up the swallow with the other rubbish and hurried onto the next street.

From that day forth, although the ghost of Sherlock Holmes never appeared again, Sherlock Holmes, the Great Detective, became a legend. His methods were adopted by criminologists and detectives. The stories of his cases as written by Arthur Conan Doyle joined the ranks of classic literature, and have never gone out of print. 221B Baker Street was refurbished into a museum; neither the flat nor the statue have ever lacked for visitors and admirers since.

And yet, from that day forth, Sherlock Holmes has always been really and truly alone.

Kara Lee started out as a science writer, then decided that the known universe wasn't quite enough. Her speculative fiction has appeared in Eggplant Literary Productions: Miscellanea and the apocalyptic anthology Girl at the End of the World. Find her online at Windupdreams.net.

What do you think is the attraction of the fantasy genre?

For me personally, the best part is being able to have it both ways, in that I can exercise my imagination and still be talking about fundamental human yearnings and desires. I especially like reading--and writing--explorations of how magic spells or supernatural abilities magnifies the proverbial human condition in ways that aren't possible in real-world fiction. More powers, more problems!

Also, I have to admit, I love the prettiness that one often finds in this genre. I'm an unrepentant sucker for lovingly rendered descriptions of beaded evening gowns and sparkly magic spells, and you just can't beat fantasy for that.