The Remarkable Account of Nain’s Revolution

by Chloe Ackerman

They say the wind used to blow in Nain. It used to topple the hats off men on their way home from work and crawl under the skirts of the girls leaning against crumbling stucco walls smoking cigarillos. It used to bring foreign newspapers and rains, circuses and seasons. The wind brought us new inventions and news of changing governments, of the world revolving around our hollow little town, and it would take with it our promises to loved ones across Mexico to send money and someday visit, and we’d pray that the wind would imbue our words with a little truth before they met old tia’s lonely, hopeful ears.

Mamá told me stories of when she was little and her mother would hang vast canvases of laundered sheets out on the line. Mamá and her brothers and sisters would play hide-and-seek between the fresh, white sheets that smelled like the juniper her mother would soak in the water. The linens would linger and glide on gusts of wind, and by the time they dried, they would be coated in a layer of fine red dust, like sails at dusk. “Why would you put them out, Mamá?” I would ask.

“They had to dry, mi hijo,” she’d say.

“But as soon as you put them out, they got dirty again!”

“And as soon as you’re born, you start dying,” she would answer. “That’s no reason not to live, is it?” And then I would spend my nights dreaming of sleeping in a dusty bed, of grit in my mouth and the priest’s ashes to ashes and dust to dust, of trying to scream through the granules in my teeth that I wasn’t dead; I only wanted to see if he’d come.

The wind doesn’t blow in Nain anymore. Mamá’s sheets hang limp and heavy, and come in too stiff to fold. Some say the wind forgot about us, wandered off to a new town and fell in love with wider horizons and sweeter girls. Others say it was never there in the first place, only in our imaginations. But I remember the day the wind stopped blowing. That was the day our fathers joined the General’s army. He wasn’t a general then, just Octavio Jiménez, another bored and unemployed local with nothing to do but start a war.

That night was vividly hot, and we slept on the tiles in the courtyard to escape our baking bedrooms. We woke to gunfire and firelight, and Mamá gathered my sisters around her while I, five years old and brave, stood watch for Papá as he ran next door for news.

It was a revolution, he told us the next morning, and the regime would soon fall. Octavio had rallied Nain’s fathers in the night, and they were to march in the morning. But Mamá would not just let him go. She reasoned with him first, pointing out that the government had never done him harm, didn’t levy unbearable taxes or start petty wars. Then, when he began to speak of injustice and common rights and people disappearing mysteriously from their beds, she begged him not to go. She told him he would be killed, and his family tossed into the street for being related to a traitor. “What will we do? We’ll starve! Your son, Roberto!” And she pointed to me as if I were more important than she or my sisters. Your son!

Papá heard none of what Mamá said. He had a fire in his veins, and nothing would quench it but fighting in the war. And he thought he was doing what was honorable, what was good for the country. He wanted a better future for his son.

Who knew back then that Octavio would win? But he did, and now he was the General, and all that was left of Papá was a memory of him standing in the street with his hat off trying to smile with the sun in his eyes no matter which way he faced, and anyway it was too hot to smile. Too hot to cry, but he thought Mamá was, even though it was just sweat. That was all we had of him, but now my sisters had their own families, their own sons to keep out of gangs and drug cartels, their own husbands to keep out of other women’s beds. Their memory of the man who left his wife to fight a battle that would better our lot was better forgotten.

There is a legend that three years after the war the wind briefly returned. As always, there are those who would tell you they were there when it happened, that the night was full of omens, like eerie singing and portentous lights in the sky. They would tell you the gust of wind was like a flurry of massive beating wings, and there was an after-breath, like whiplash, that smelled of rich perfume and salt water. And they would tell you that in that fragrant gasp, a message was whispered, faint and awed, “He’s here,” and then the wind vanished.

But there is always an old seer or a drunken beggar to tell the story of things that happen when the rest of us sleep, and who ever believes people like that?

And so everyone got on with their lives without the wind, without a generation of men. Mamá worked harder, and every white thing in the town turned yellow like old photographs, and the rest of the world fell out of our minds.

In those days, all the men left in Nain would sit on their doorsteps drinking Marquez’s home-brewed beer, even the General, who wasn’t supposed to condone these things, but did them anyway because he pretended to be One of Us. He was afraid of us and wanted to keep us close, know our every move. We spent a lot of time on our doorsteps in those days, waiting for a change to come our way. “Viva la Revolución” would show up in red once in a while on the side of the church, and the altar boys we used to beat up would have to scrub the words off with lye and scalding water. The General didn’t acknowledge these words, just smiled a greasy smile with his rotting, gold-capped teeth and shook hands with men who thought his palm felt too soft, like a woman’s cheek. Later he’d take some old veteran who looked at him wrong out behind the church and flog him to teach the rest of us a lesson.

In those days, we slept long past our siestas and passed the days shooting at the rats as they slunk into the street. I bet you twenty pesos you can’t get the next four in a row, someone would say.

You haven’t had twenty pesos in thirty years, buey. You’ll give me one night with your wife! And then a scuffle would break out, but they’d get too tired before the knives were drawn, so none of us bothered to lift our hats from our eyes and cheer.

But that day a rat mistook me for a hole in the wall as I dozed on the doorstep with my frayed straw hat over my face, my boots kicked off and my shirt soaked yellow with sweat. I wore that shirt because it made me look like I worked hard. Mamá was toiling through her siesta like she did most days, laundering the General’s silk pants and embroidered jackets. It was Sunday and Mamá called him a rat just like the one on my chest, but the General was already pulling the trigger by the time anyone realized the gun was pointed at me.

When the man told me to get up, I got up, and the whole town was there. Something smelled like burning flesh, and I felt hollow and empty, like a well gone dry. Mamá was sweating, or maybe they were tears, and someone had dressed me in white – real white, not Nain white. Someone called me God. Or him. There was dirt in my mouth, but I began to talk. “You! I’ve heard of you! I’ve been waiting for you, I knew you would come if I….” He was looking at me, and I had never felt so ready to till a field, or better yet, turn my hoe into an ax and rally an army behind this man. I was about to pledge my life to him, thinking this was it. This was the one we’d been waiting for. Here was our revolution.

And I started to say so, but then he took my arm and led me to Mamá. “Here, Señora,” he said, and had to let go of me to support her when her old knees buckled. “He’s ready for work. You take the day off.” Then I noticed the General twisting his moustache and I knew he was going to have at the man because it was Sunday and the General hated it when people worked on Sunday. Unless it was for him.

The General never got his chance, though, because at the moment of uneasy silence that comes just before good men are murdered, a newspaper tumbled loudly across the road. The whole town watched the newspaper as it somersaulted over the General’s feet and plastered itself across someone’s legs. It was Esperanza Ávilar, and she pealed it off and began to read an article about an army of peasant women in Columbia who stormed Congress armed with corn cobs and rifles and pulled their corrupt sons into the streets to beat them with back hoes, something they said they should have done long ago.

A sigh accompanied her as she read, a sigh of relief, as if something great that no one believed possible had been accomplished. And Esperanza read of miracles, of tyrants laying down spiked scepters and political prisoners walking free, of whole villages adopting orphans and drug lords burning their fields.

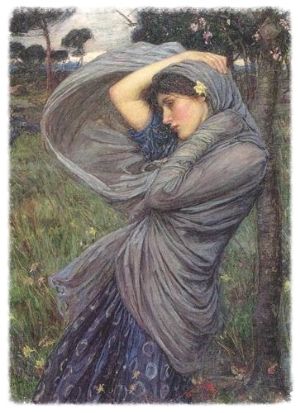

The sigh stirred loose hair and tickled bare arms. It dried salty sweat into cool skin and meandered through the gaps and folds in our clothes to soothe our burning marrow. It ran itself out and came back again, sending dust and loose ribbons into frenzies of frantic dancing.

The General never did get his chance, because as Esperanza’s voice tapered off, the wind began to blow.

It filled our lungs before we knew what was happening and we breathed for the first time in nearly forty years, a gasp filled with myrrh and sea salt, and someone whispered, “God has come to help his people.” We closed our eyes as the wind played on our faces, listened intently to the sound like waves as the breeze weaved through the pine boughs.

And then we gasped collectively as a scent hit our tongues – the smell of dust and ozone, of old land, and the sense of electricity raising every hair on every neck in town for the first time in four decades – a storm was coming.

But the wind’s nature is one of persistence, and no storm would steal its stage. It gave up being a welcomed caress and charged us like a bull, so that we all swayed on our feet and the General landed on his back. The people began to clamor, and the man’s followers were looking frightened and confused. I hadn’t noticed them before, but I did notice the General picking up a hefty rock and weighing it in his palm. The man noticed it, as well. So amidst the people asking his name or for the winning lotto numbers and a more faithful husband, he turned to the street that cut through town, the one littered with the corpses of unfortunate rats and most of my blood, and he walked past the stucco houses and shops stained the color of dirt so they all ran together like a watercolor. The General’s stone fell short.

As the man made his way through town, I struggled after him, holding a hand to my hollow chest. “Let me join you.”

He chuckled. “You want to start another war. I’m here to start a revolution.”

As he began to walk away, an arm of the wind shoved me forward and I grabbed his sleeve. “Wait,” I asked timidly, granules sticking in my teeth. “Will I die again?”

“I think that’s up to you.” He turned towards the edge of town, his followers closing in around him. And then the rains began, swallowing up the whole town as the distance swallowed him. We were drenched in moments, streaks of dirty water running down our faces and the crumbling walls. Rivulets turned into rivers and ate away at the ground, forging arroyos and sink holes and unearthing things long-buried. The ground was too dry and didn’t remember water, and so in the flash floods coffins and corpses floated through the streets, bobbing like dancers at a wedding feast, and we all thought the end of the world had come.

But eventually the loose dirt was washed away and the earth learned to drink the rain. Nain turned green. I went to work so Mamá could take her siesta, and the wind blew the sweat away so I didn’t look like I worked hard, but people knew I did anyway. The other men wandered back into the fields and workshops, picking up rusty tools and giving them a test run before striking the ground or anvil or wood. The General didn’t change, though. Not everyone changes. But our revolution had come, and the General was powerless against it. Dead men had risen and danced in our streets, and then they had gone back to work.

Chloe Ackerman hails from the Land of Enchantment but currently resides with her dog and three rats in the much rainier (but no less enchanted) Northwest. She has edited or contributed to a small number of literary magazines and anthologies, but is currently putting everything she has into a doctorate in clinical psychology. She hopes to one day be both a famous author and a renowned psychologist, because she believes in having it all.

What do you think is the most important part of a fantasy story?

When I was in high school, I wrote a poem I thought was fantastic. I showed it to my creative writing teacher, and she said, "But Chloe, there's nothing underneath it." She was referring to the deeper meaning, the truth of human experience I was completely failing to include in my pretty words. There are so many important parts of a fantasy story, but I think the soul of fantasy is how it connects to our experience in a way we can't in our everyday world. Without that, the story can still be good, but it's easy to walk away from because there's nothing to connect to, nothing to leave the reader breathless and homesick for the truth in the world they just left.