Fire and Lye

by Stefan Milicevic

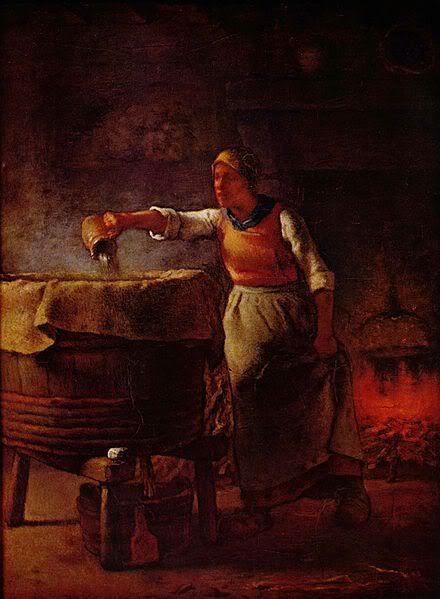

The scholar was dying on our table, but all I could hear was master Helveskar’s voice, urging me to churn faster.

“There is a right way to go about it. Hold the paddle upright, you are a soap maker, not a dockside whore. You make soap. You do not pleasure a sailor.”

I thrust as hard as I could, ignoring the calluses and sores that ridged my fingers. Sores heal. They always did.

“No.” Master Helveskar’s voice was like a knife wrapped in silk. He swung his quirt at me. There was a sharp hiss and a flash of pain blazed over my cheek. Blood trickled down my face. “That man will die if you don’t churn faster.” He cracked the quirt once more. “What is your name, girl?”

“Lye,” I said, gritting my teeth.

“And what is your calling?”

“I make soap.”

Master Helveskar nodded his approval, quirt in hand. The smells of blood and rotting guts argued with the smell of burning fat and ashes. I churned faster, my chains cackling as if in mockery. I ignored their cruel glee. One day I would undo them and plant a knife in my Master’s back.

Under my breath, I murmured the name of fire, stoking the flames that burned under the kettle. It was one of my few treasures. The little pinch of magical spice that seasoned my otherwise bland and lonely life. The flames licked upward, heeding my call.

I stuck the paddle into the kettle. Two breaths later it still stood erect. The soap was ready. Master Helveskar pushed me aside and scooped up some fresh soap with his ladle.

“There’s no time for it to dry and harden. The fresh stuff is more potent anyway.”

He turned to the dying Magister and dabbed the man’s head with a dirty cloth. Flies dotted his soiled brocades like tiny, black brooches. Master Helveskar poured the soap into the ruin that was his stomach. The scholar’s scream held no horrors for me. I had long been accustomed to the agonies of common men under Master Helveskar’s apprenticeship.

I watched the scholar moan both with pain and relief, as my master poured the scalding soap over his wound and rubbed the gooey mass into the scholar’s intestines. Soon his flesh would mend.

Alveista, once the city of gods, had been reduced to a sprawling ruin. The spires jutted out of the ground like rotten teeth, their glory as houses of worship but a bone bleached memory in the minds of few. The gods had been thorough in their punishment of the rebellious mortals. The doom they had unleashed seemed boundless in its fury, for the backlash of their powerful magicks crippled their bodies, until we were left. The slave race. Sentenced to live or to die according to the whims of all mortal remnants of the doom.

The sun sank beneath the horizon while I was watching how peddler and peasant flung offal and rotten vegetables at a caged slave. I snorted. The fault was his own; I had my own chores to take care of.

I sat next to the ashbin, scraping at the spidery tattoo that marred my body. My master decided to chain me outside while he treated the scholar’s wounds. Bit by bit I flayed off my skin, cutting my arms into ribbons. As soon as I had carved out a substantial amount of the tattoo the flesh of my forearm burned. Layers of skin sprouted like tufts of grass, mending the wound. The intricate lines of ritual ink were still intact, as if they have never seen the edge of my knife.

Sores heal. They always did. For a moment I considered cutting out my heart, but dismissed the idea. It was a coward’s heart. It belonged in my chest.

Such was the fate of the slave race. To be beaten, whipped and flensed, only to heal again.

A dull, remote part of my mind was grateful that my gravest concern was the stench of fat and ashes while making master Helveskar’s healing soap, but another made me raise my head and behold the poor sod, exposed to the jeers of the mob. I cursed him for his ham-fisted escape attempt and because he had the courage to do what I yearned for. At least he had the assurance that he failed. He knew that execution was nigh. I still trembled at the mere thought of my master’s quirt.

My name is Lye. I make soap. I repeated the words in my mind like a prayer.

A deep, tenebrous voice interrupted my solitary task. “I owe you my thanks.” The scholar squatted next to me. His face was round and his hair sleek, and tangled like a bird nest. “Without your soap I would be dead. You possess a precious gift.”

“It is a curse,” I said raising my arm to show him the tattoo that brandished me as a slave. “I healed you not for love, but for the fear of my master’s quirt, and the all crueler instruments of torture that he owns.”

He blinked and said, “But heal me you did, all the same. I am obliged to return the favor.”

I tugged at my chains making them snarl. “Can you undo these? If not, stop bothering me, magister.”

He started at the sight of chains as if I brandished a weapon at him. I found him a vexing man. Like most scholars’ his knowledge came only from books. He was the type who would read dissertations on agriculture and want to grow beans, never having seen plough nor field, or an honest day’s worth of hard work.

Again he blinked and assumed a somber expression. He spoke my suspicions before I had the chance to.

“I am no magister,” he said. “Just an apprentice.”

I gave a bitter laugh. “I assume your purse suffered.” The mere thought of my master’s face when he discovered that the magister had been nothing but a poor apprentice was enough to sweeten my day.

“Quite a bit.” His gaze trailed off as if he was immersed in solving a mind-racking equation. “Helveskar was quite furious too. At least I think he was. Until I offered to make him an etching acid in the foreseeable future.” He winced. “But making etching acid requires caustic substances. I think I will not go near those after today’s accident. I nearly killed myself.”

I did not reply, my gaze fixed on the cage and the poor soul who was bound to die soon. The silence was broken by the wind whispering through the stuccoed ruins of Alveista.

The apprentice reached for my hand. “Still, I would very much like to repay your kindness.”

I withdrew it and pointed at the cage. “See him? I want what he wanted before they put him in the cage.”

The apprentice lapsed back into his annoying habit of blinking like an ox.

“I want freedom,” I said.

The apprentice’s face turned blank like slate. His brow furrowed and for a moment I believed that he was a member of the Collegium.

“There might be a way.”

“Is that so?” I said, trying to not let hope bleed into my voice.

“Yes. In the days before the Collegium magic was a common phenomenon. The process of unleashing magic is a difficult one, but the basics can be broken down to this: To utter the true name of a thing or person is to control it.”

If I were to find out Master Helveskar’s true name I would repay him every thwack of his quirt doubly.

“I must admit that I dabbled with such things in my youth,” the apprentice said, his voice but a whisper. “I know a few names, but my command over them is tenuous at best.”

“I know the name of fire.”

His eyebrows shot up. “Fascinating. It must come naturally to your kind.”

I felt how my entire face wrinkled like an old sheet of onion paper. “Yes, it surely does. My kind also enjoys beatings and public humiliation.”

A spark of shame lit the apprentice’s bovine face. “I meant no offense,” he stammered, scrambling for words in that awkward manner of his.

“Never mind,” I said. “Teach me the name.”

Then he spoke a word that sounded like clashing swords and my chains slithered and rattled.

I twitched with surprise.

“That was no parlor trick,” I said, my voice slow like rolling honey. “I felt the tug of iron on my skin.”

The apprentice’s lips curved into a smile that told me that he was not used to praise. “If you master the name of iron, one day you will be able to break those chains.”

My heart beat so hard I felt it strike my ribcage. A warm feeling lit my chest. To be free of both my master and my chains. I relished the idea like a sweet drink of water, and the more I savored it the thirstier I became.

“Do you accept this gift?”

I nodded slowly. The apprentice brought his lips to my ear. The warmth of his lips tickled my neck as he spoke, his lips uncomfortably close to my skin.

The word he spoke was the snarl of chains and the song of swords. It was the sound of clinking coins and the deep voice of ore waiting to be unearthed.

The sound of it went through me, deep down to the marrow of my bones and stayed in my mind as if etched in steel.

“One day the sounds will turn into a word. Keep it close to heart and it will reveal itself to you.”

I looked at the apprentice again. His round attractive face. His curly, flamboyant hair. A gruff voice nudged me from my reverie.

“Girl.”

I looked up and saw Hobbard, the cobbler. Next to him stood the boy I saw in the cage a few moments ago, slave collar around his neck.

“Since this boy here don’t want make no shoes, I’ll let him ‘prentice for the soap maker. Where is he, girl?”

I nodded towards the door. “He is inside.” I snuck a glance at the boy and saw fear spreading on his sallow face. At least he had been fed well. Hobbard knew the price of good fat.

Yet he wore his resignation like a mask. I could respect that, for it required a queer sort of courage found only in slaves.

“Very well. Get moving, boy.” Master Hobbard dragged the slave boy inside.

I felt ink-black contempt spread in my chest. Then regret washed over my mind as I gripped the handle of my knife.

I should have stuck it into that bastard Hobbard’s black heart.

“What is wrong?” The apprentice’s head darted between the shops entrance and me. “Soap making is a respectable business as any. Especially your master’s soap.”

I snorted. What else to expect of a person whose knowledge came from nothing but books?

“They don’t seem to teach you common sense at the Collegium.”

“What do you mean?”

“To make soap you need lye and fat.”

“That is common knowledge,” the apprentice replied.

“From what do you think does my master render his miraculous, healing fat?”

For days I was savoring the sound of singing iron in my mind. When I cut the congealed mass of soap into bars I heard the clash of swords, when I scrubbed the kettle I relished the sound of brittle chains and kept undoing them in my own private fantasies.

The name was like water, without constant shape or form, yet I heard it whisper to me like a babbling brook, inviting me to call its name. Yet whenever I opened my mouth the word fled or froze or caught in my throat like a fishbone.

But it did not roughen my patience. Naming was much like making soap. It took practice and mastery.

One day I would undo the chains and be free, at least as free as one of the slave races could be.

One evening Master Helveskar sat down on his stool and watched me churn the thick, sudsy mass of soap. I tried to pay him no mind for his scrutiny always tensed my shoulders, and made my fingers thick and clumsy. I think I was churning the cobbler’s prentice since the kettle’s contents smelled faintly of old leather and polishing fat.

I kept churning and the fire crackled. Whereas my mastery of the name of iron was far from perfect, I found that practice strengthened my command over the flames. Once the heat burned against my face, but with each passing day it felt more like a lover’s caress. A little gentler. A little bit more arousing.

I snuck a glance at master Helveskar, half expecting him to admonish me for my lack of attention, but I found him nod his approval. The quirt was nowhere to be seen.

A rare compliment indeed.

“Lye.” He spoke my name with a hint of pride. I did not like the sound of it. “You have served me well, and although at times I find your concentration lacking you have become a fine soap maker.”

Upon hearing those words I almost dropped my paddle. Was this another game of his? To coax a smidgen of pride from me, to only let me know what a fool I was?

“Thank you, master,” I said. “You flatter me.”

He shook his head. “I do not. I think that you have learned all I can teach you. It is time to move on. For both you and me.”

I released the paddle and turned to face Helveskar. His lips curled into a smile, as cruel and crooked as a knife.

“You see, Lye, the slaves are becoming a humble and broken lot.” He shifted on his stool as if he was telling his grandchild a story. “But as time went by they learned their place. That is good, in some ways. But bad in others. Certainly bad for me.”

I embraced the song of iron, the clashing steel and cackling chains. I embraced them like a charm, but they seemed pale and silent sounds when I saw the glint in Helveskar’s eye.

“Since the cobbler’s boy I had had no new slaves brought in. No fat for our soap. But I fret not. It is time I retired. After a last batch of soap bars, that is.”

He rose from the stool and approached me with not a quirt in his hand but a knife that he procured from the folds of his master’s robe.

“No...” My protest was half a whisper. I edged slowly towards the exit, but the snarling chains reminded me that I would not make it far. The man who had been my master shook his head.

“You never learn, girl. Tell me your name.”

“My name is Lye. I make soap.” The words came unbidden and I cursed myself.

“Indeed. Lye is a crucial ingredient in soap making, girl. Do not make this more difficult than it needs to be.”

My eyes were glued to the knife in his hand. The pitted piece of steel that had bit through many a slave’s flesh. I gritted my teeth and swore that it never would know the taste of mine.

I grabbed the paddle and tossed it at Helveskar. He shielded his face with his elbow, and that was when I seized my chance. I took a length of chain and slapped him at his temple, sending him to the ground. I sat on his torso and proceeded to wind the chain around his throat. He groaned and I yanked the chain as hard as I could. His eyes were bulging like bubbles on a stew, his face taking on a disturbing shade of purple.

Then I heard not a word, but a name come from his chapped lips, a name as sharp and beautiful like a jagged piece of obsidian.

“Marisella!”

The word knocked the breath out of my chest. My muscles slackened and I felt to the ground with a dull thud. Helveskar was already up again, dusting off his lavish robes. My mind sloughed through morass.

“Foolish wretch. Every slave is sold with a name. A true name. Not the pesky monikers we bestow upon you.”

He kneeled next to me and drove the knife into my thigh. Pain flashed through my body, hotter than the caress of flame. Steel tore through my flesh and I felt blood seep out of the path that the knife carved. My wounds wept and I wept with them. I was never meant to be a master of names, but a bar of soap. My name was, after all, Lye. I sunk into the dream world, the only place where I felt safe from the pain.

In my dream it smelled of smoke and burning hair. I heard the sound of toppling walls and the keening of children. I saw an arc of light tear the seams of heaven. Alveista was a silver torch that lit up the night.

And then there was silence.

Soon the survivors crept out of the rubble and built and toiled and enslaved.

And then I knew who I was.

My eyes snapped open, the wound in my thigh nothing but a wet memory. I spoke the name of fire and it came to me naturally like a song. The flames leapt and danced, engulfing the kettle, filling the room with the smell of ash and rancid fat.

Helveskar swiveled his head toward the kettle and his eyes grew wide. I seized the moment and crawled toward the water basin, where I used to wash my hands after hours of toiling over the kettle making soap of my brothers and sisters.

“No!” Helveskar yelled. He knew what I was about to do. It was one of the first rules he taught me. Never pour water over burning fat.

He plunged the knife into my back, but pain had ceased to mean anything to me. There was only the smell of smoke and burning hair and the sound of keening children. I knocked over the wash basin. Fire and water met and the workshop was ablaze with curtains of fire, dancing reds and flickering crimsons.

I watched how the body of my master turned into a smoldering mass of flesh and bone. I felt the fire embrace me hungrily, tugging at my skin and cleansing my soul. Scabrous burns sprouted all over my skin like lichen, purging my slave tattoos. Burns heal. They always did.

I went out into the street where people had already gathered around the burning workshop. They looked at me and slave, master and merchant alike dropped to their knees.

They did not see a soot-covered girl with blisters on her fingers. That had been a foolish girl, who tried to claim a name that did not belong to her.

In front of the burning workshop they started to chant my name.

My name is Suulani. Scion of Fire.

Stefan Milicevic is an author of fantasy, horror and science fiction who likes to talk about himself in third person (which makes him sound kind of important). When he is not involved in a mind-racking game of Go or Shogi, you can find him tinkering with a new story, or hanging out with his friends. He is also fluent in four languages and can't waltz to save his life.

What do you think is the attraction of the fantasy genre?

The sheer possibilities and depth of the subject matter. Well-written fantasy stories are a crucial part of the modern myth.

0 comments:

Post a Comment